From the mid-1980s until the first months of the 21st Century, a coalition of desert tribes and non-Native activists worked to keep the state of California from siting a low-level nuclear waste dump in the Mojave Desert, on land sacred to at least five tribes, above an aquifer that drains into the Colorado River. Philip Klasky, an instructor at San Francisco State and a resident of the desert in San Bernardino County, played a crucial role in that campaign, which succeeded against all odds. Phil's story is a lesson in how people working together can beat those odds. He also taught us at 90 Miles from Needles the importance of Native peoples taking the lead in land-based campaigns.

Phil died unexpectedly earlier this year. We are grateful to The Mojave Project for allowing us to use their recorded interview with Phil, and to our friend Matthew Leivas of the Chemehuevi Tribe for sharing with us the Salt Songs he sang at Ward Valley in May to honor Phil.

Become a desert defender!: https://90milesfromneedles.com/donate

See omnystudio.com/listener for privacy information.

Like this episode? Leave a review!

Check out our desert bookstore, buy some podcast merch, or check out our nonprofit mothership, the Desert Advocacy Media Network!

UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT

0:00:00 - (Alicia Pike): This podcast was made possible by the generous support of our Patreon patrons. They provide us with the resources we need to produce each episode. You can join them at 90miles from needles.com Patreon.

0:00:25 - Bouse Parker: The Sun is a giant blowtorch aimed at your face. There ain't no shade nowhere. Let's hope you brought enough water. It's time for 90 miles from Needles, the Desert Protection Podcast with your hosts Chris Clarke and Alicia Pike.

0:00:43 - (Phil Klasky): Ward Valley is near Needles, California, about 18 miles from Needles, California, 18 miles from the Colorado River. The federal government has a policy of locating hazardous waste sites near low income and communities of color. And because it was considered to be in the middle of nowhere, because the local residents are American Indian tribes, they wanted to put this radioactive waste dump above an aquifer that communicated with the Colorado River.

0:01:15 - (Phil Klasky): The radioactive waste would percolate through the land to get to the aquifers. My name's Phil Klasky and I teach American Indian Studies and Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University. I'm also a consultant to the Cultural Conservancy, a non profit indigenous rights organization.

0:01:45 - (Chris Clarke): Hi, welcome to 90 Miles from Needles. I'm Chris Clarke. Almost 30 years ago, back in the spring of 1995, Phil Klasky came into my office in Berkeley, California where I was editing an environmental newspaper. He introduced himself, said he was working on a campaign to keep a nuclear waste dump from being established in the Mojave Desert on land sacred to the local tribes and far too close to the Colorado river for anyone's comfort.

0:02:17 - (Chris Clarke): He said the firm behind the plan, U.S. ecology, which had a series of leaking dumps across the country, planned to put low level radioactive waste in deep unlined trenches in Ward Valley, California. He wondered whether I might be okay with him coming up with a bunch of articles from experts on the topic. Native writers, physicists, geologists, hydrologists, biologists, non native campaigners, people involved in the anti nuclear movement.

0:02:52 - (Chris Clarke): What if he put a whole bunch of these articles together? He asked could I devote an issue of the paper to the Ward Valley campaign and would I be able to print 10,000 extra copies so that he could distribute them amongst among people he wanted to raise awareness with across the state? I told him I was enthusiastic about the first part and wasn't sure I could do the second part. And then he promised to raise the funds to print the extra copies and we were set to go.

0:03:18 - (Chris Clarke): That was how I met Phil Klasky. Now if Phil was here, he would caution me against reading too much into his actions. He would say it wasn't him that was important, it was the cause. He was just trying to do what he could, and there is a way in which he's right, or he would be if he was here, but he's not. We lost Phil earlier this year, unexpectedly. The words you will hear from Phil in this episode come from our friends at the Mojave Project, a wonderful multimedia art, culture, history, science and politics project by Kim Stringfellow, San Diego State University.

0:03:57 - (Chris Clarke): Google the Mojave Project or go to our Show Notes we're indebted to Kim for letting us use the audio she caught of Phil talking about the Ward Valley campaign that he influenced so greatly. If you're sitting in the desert right now, or standing, walking, whatever it might be, driving, or if you're anywhere else for that matter, I'd like to try a little exercise with you, if that's okay. If it is safe for you to close your eyes, do not do this if you're driving, but if it's safe for you to close your eyes, you feel free to do so.

0:04:28 - (Chris Clarke): But whether your eyes are open or closed, pay attention to your breathing in. Out. You breathe in and atmosphere rich in oxygen, courtesy of plants, including thousands of different species of desert plants, courses through your lungs and into your bloodstream, keeping the little chemical factories of the trillions of cells in your body going. Breathe out. And some of that oxygen is replaced by carbon dioxide, which you've generated in conducting your metabolic activities and which is food for the plants around you, including desert plants.

0:05:07 - (Chris Clarke): When you breathe in in the desert, you take part of the desert ecosystem into yourself. When you breathe out, you give some of yourself to the desert ecosystem. Sometimes it seemed as though working to protect the desert came as naturally to Phil as breathing in and breathing out. This episode of 90 Miles from Needles is devoted to Phil, not just because we lost a friend and we miss him, but because he, like all the rest of us, was a complicated person with joys and sorrows, a busy schedule, a lot of things to keep track of, many reasons that it would have been smart for him to not get involved in campaigns that took far longer and far more energy than he imagined.

0:05:51 - (Chris Clarke): And yet he did the work anyway. There is no superpower needed to be an activist. There is no exceptional quality you need to protect the desert. You can be a person rife with insecurities and minor embarrassments who has way less energy than the tasks of the day demand. Our one superpower is the network of relationships we have with one another. It's a web that predates the World Wide Web runs back in fact thousands of years.

0:06:25 - (Chris Clarke): A network of relationships between people. Desert activism is about people. It's about other things. It's about water, it's about species, it's about attitudes and philosophies. But at its core, desert protection activism is about people. So in talking about Phil in this episode, we memorialize a friend for sure. But we take his passing as an opportunity to remind ourselves that it is people that do this work.

0:06:53 - (Chris Clarke): And none of us are alone, as isolated as we sometimes feel in the desert with its 0.03 people per square mile. Those of us who work to defend the desert are not alone.

0:07:16 - (Phil Klasky): Ward Valley in the Mojave language is called Silia AIs. And it's very interesting to think of a map of the area. Who gets to name it, what value it has. Silli AIs is a gathering place. The name actually means a gathering place of scroobe, mesquite and sand. And was part of an important social ritual where different bands of Mojave would come together. They would have a huge feast. They'd roast the buds from the yucca and bring foods together. And it would be a place where young people could meet.

0:07:55 - (Phil Klasky): And so Ward Valley was not just an environmental issue, it was a cultural issue. It was part of Native Americans attempt to maintain their culture. It's important to understand that this whole history came together at Ward Valley. When I first became involved in the Ward Valley issue, I did so as an anti-nuclear activist, someone who had some experience. But in time, after working with the American Indian tribes, I felt that myself and other non-Indians who were working on this project were being influenced by the profound relationship that these tribal peoples had and have with the land.

0:08:44 - (Phil Klasky): First time I was invited to a meeting about the Ward Valley dump. Some friends of mine who are anti-nuclear activists had met with some of the tribal folks and had arranged for a meeting out at the site. We got there, there was a large bonfire and there were members of the five tribes. And I remember one man in particular, Chance Esqueira, who was a game warden for the Chemehuevi tribe, said some things that really made an impact on me. He said, who is going to speak for the desert? Tortoise for the Mojave, green rattlesnake for the golden eagle, the horn toad.

0:09:26 - (Phil Klasky): He said, I am, we are. US Government has chased us off our lands, put us on reservations, and now they want to contaminate our sacred lands. They don't understand what sacred is and what it is to us, what it means to us. And I began to understand that people who are born in an area where they can see their place of origination, the Spirit Mountain is north of Needles, California. When the Mohave wake up in the morning, they look north and they see a place where their spirit mentors reside, have a different relationship with the land. This was not going to be a sort of the expected kind of environmental campaign.

0:10:18 - (Phil Klasky): These were people who were prepared to lay down their lives to protect this place. And during the 10 year campaign, when I first began, I had no idea this was going to be 10 years. I thought, okay, two years. What we'll do is we'll expose the fact that Ward Valley, where they wanted to put this radioactive waste dump, is above an aquifer that communicated with the Colorado River. That was a crazy idea that this thing would be stopped. Well, it took 10 years.

0:10:49 - (Phil Klasky): No idea the journey that all of us would be taking, Indian and non Indian alike, in order to stop this radioactive waste dump. And thank God we were successful. Took a lot to do that. And a lot of people along the way sacrificed a great deal in order to protect Ward Valley. We were trying to figure out how in the world can we stop this radioactive waste. The federal government under the Bush administration was prepared to transfer the land, federal land, to the state of California. The governor at that time, Pete Wilson, was a pro nuclear advocate.

0:11:29 - (Phil Klasky): And we were trying to figure out what laws we could use. We looked at laws that protected American Indian cultural and sacred sites. The problem is some of those laws sound very good, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. But the enforcement mechanisms are extremely weak. We knew that we had to develop a grassroots presence at Ward Valley. And for many years there was an encampment at Ward valley, sometimes with five people, sometimes with 500 people there.

0:12:03 - (Phil Klasky): And I remember in particular a study that was done by a US Geological Survey federal employee, Dr. Howard Wilshire, that showed that Ward Valley was right above an aquifer. And there were five subsurface pathways to the Colorado River. And eventually radioactive waste buried in containers that don't outlast their contents would leak and make its way into the Colorado river. Well, when Dr. Wilshire came up with this analysis, the response of the federal government was to fire him.

0:12:43 - (Phil Klasky): He's a whistleblower. It took Dr. Wilshire quite a few years to sue the federal government. When he got his job back, he went to his office for one day and then quit. But he proved the point that this radioactive waste dump would eventually contaminate the Colorado River. At one of our meetings in Needles. At the end of the meeting, Llewelyn Barrickman called me over and sat me down and said, Phil, there's something I want you to think about here.

0:13:14 - (Phil Klasky): Ward Valley is headquarters for the desert tortoise. Okay, what does that mean? He says it's your job to find out. I found out that the desert tortoise, who's remained relatively unchanged for the last 65 million years, lives to 120 years of age, is an incredible creature, had been listed on the endangered species list, and that as soon as a species is placed on the endangered species list, the federal government has a two-year timeline to designate critical habitat for that species. It's not enough to just list it on the endangered species list.

0:13:57 - (Phil Klasky): The government's job is to designate that critical habitat needed to protect the desert tortoise, and that this radioactive waste dump was going to go into a place that could potentially be part of that critical habitat. I also learned that the federal government, as it usually does, had contracted the study for the designation of critical habitat to a group of scientists. There were 12 scientists who had authored a study, and I called every single one of them.

0:14:34 - (Phil Klasky): I wanted to get my hands on that study. Was Ward Valley part of that critical habitat? Because if so, who? We could then use the Endangered Species act to stop the radioactive wisdom called one scientist can't talk to you, another one, I can't possibly let you know the results of that study. I'll lose my government contract or I'll lose my job. One by one, going down the list of these scientists. And I was very transparent. I said, fighting against this radioactive waste dump. I have a really good idea that Ward Valley is critical habitat, but I need the results of the study that you're working on in order to take it to court.

0:15:15 - (Phil Klasky): Some of them would not return my calls or even hung up on me. I was down to the last scientist, who was head of the Department of Biology at University of Nevada at Reno. Went to his office, and I think he thought that maybe I had a wire on me, because when I walked into his office, he said, Mr. Klasky, I cannot give you the results of this study. He then got on his phone, called his secretary, couldn't hear what he was saying, and a few minutes later she came in the room with a brown paper bag, handed it to me.

0:15:52 - (Phil Klasky): I thanked the biologist, went into the parking lot, sat down, opened up this study and read the fateful words. Ward Valley is the most robust habitat for the desert tortoise in the entire Mojave Desert. We had two young, enthusiastic and affordable attorneys who worked with U.S. environmental attorneys. And we were in court a week later using the Endangered Species act to stop the federal land transfer at Ward Valley.

0:16:26 - (Phil Klasky): Well, we thought we won. We thought that this was it. The Endangered Species act is actually one of the strongest environmental laws on the books. But we were premature. Shortly after we won in court and got an injunction against the federal land transfer which was a prerequisite for the construction of the dump, we learned that the senior senator from Alaska, Frank Murkowski, who received more donations from the nuclear power industry than any other senator, had attached a rider to the budget bill that exempted Ward Valley from the Endangered Species Act.

0:17:12 - (Frank Murkowski): The senator from Alaska is recognized to speak for up to 15 minutes. Mr. President, good morning. Let me review a little history. Back in 1980 and 1985, Congress gave the steps necessary to each state for the responsibility for low level radioactive waste disposal. Having studied the rules of the procedure some years ago, the state of California begin the long process to site a low level facility for the waste generated in California and its other compact states, including Arizona, North Dakota and South Dakota.

0:17:55 - (Frank Murkowski): While some eight years went by, Mr. President, during the licensing process costing more than $45 million, the state of California finally completed its task, awarded a license for waste facilities facility at Ward Valley out in the Mojave Desert. Now we've seen opponents of the project ranging from the antinuclear activists to some of the West Hollywood movie stars who continue to oppose Ward Valley at seemingly every opportunity.

0:18:28 - (Frank Murkowski): So they continue to oppose, continue to litigate, continue to delay. At the very least, the project opponents will ask for another supplemental EIS to consider any new information, a new basis for further litigation or new strategies for delay. These delays would just simply go on and on and on.

0:18:50 - (Alicia Pike): And we'll be back after the break.

0:18:52 - Bouse Parker: Here's a 90 Miles from Needles public service announcement.

0:18:56 - (Alicia Pike): We just want to take a moment of your time to remind you that Joshua trees are in trouble and we need your help. On June 15, the California Fish and Game Commission will take a vote on whether or not to list the Joshua tree as threatened. And we need your help to persuade them to do the right thing. Get your comments in by June 2nd. 90 miles from needles.com Joshua will take you to an action alert where you can make your feelings known to the Fish and Game Commission should you miss the deadline of June 2.

0:19:24 - (Alicia Pike): You can still make comments through June 13, but it's best to have them in by the second. It may only take 90 seconds of your time to fill out an action alert. But it's protection for the Joshua Tree for the rest of all of our lives. For more information, listen to episode nine of 90 Miles from Needles where we talk extensively about the Joshua Tree protections. Once again, that's 90 miles from needles.com

0:19:46 - (Alicia Pike): Joshua.

0:19:52 - (Petey Mesquitey): Hello, I'm Petey Mesquite, host of Growing Native from KXCI Tucson. Each week since 1992, I've been sharing stories, stories, poems and songs about flora, fauna, family and the glory of living in the borderlands of Southern Arizona. Recent episodes of Growing Native are available@kxci.org Apple Podcasts and PRX. The desert is beautiful, my friends. Yeah, it is.

0:20:21 - (Chris Clarke): Do you have a desert related podcast or website or newsletter or something similar that you'd like us to promote? Let us know. 760392 1996.

0:20:33 - Bouse Parker: You're listening to 90 Miles from Needles, the desert protection podcast. Friends don't let friends paint their houses black.

0:20:41 - (Phil Klasky): And we decided we are going to have an occupation of Ward Valley. The native people came up with that idea. They said, this is our land, we're going to occupy it and we are prepared to defend it with our lives. The Bureau of Land Management 1995 gave us a deadline. They were going to come and arrest us all. We had to vacate the land. And because the federal government was going to conduct a test to determine how quickly the radioactive waste would percolate through the land to get to the aquifers.

0:21:24 - (Phil Klasky): But we were tired of the tests, and we didn't trust them. And so we stayed on the land. When D Day came, when they were going to come and arrest us, right outside the entrance to our encampment were 20 buses, Sheriff's Department buses, you know those buses with the, with the bars on the windows, 50 federal rangers, their belts bristling with those plastic handcuffs. And the night before, we were consulting the elders. What do we do about this confrontation now? The non-Indian activists had a strict nonviolence code.

0:22:04 - (Phil Klasky): We'd been very much influenced by the nonviolence code of the anti-nuclear movement. But we couldn't guarantee that the Indian folk would not react and do whatever was necessary to protect their elders. The elders said, okay, what we're going to do is hold a religious ceremony. That's the best we can do. And in fact, they sang their sacred bird songs, salt songs and creation songs all night long before the day that the law enforcement was going to come and take us away.

0:22:42 - (Phil Klasky): And in the morning, the federal rangers were faced with concentric circles of Indian and non-Indian activists. In the very center were about 25 elders who'd been singing all night long. Surrounding them were native peoples from nineteen tribes in the American Southwest. And surrounding them were the non-Indian activists. We also had the wherewithal to invite the major television, radio and newspaper stations there because, you know, the media loves a confrontation.

0:23:17 - (Phil Klasky): And as the Rangers were getting prepared to arrest us, I walked over to a gentleman who I recognized as being part of the president's office and was communicating with Washington D.C. and I said, you sure that you want, on camera federal Rangers arresting Indian elders participating in a religious ceremony? He went off, consulted his superiors. Ten minutes later, Bart got a command, and all those 50 Rangers turned right around and left.

0:23:58 - (Phil Klasky): And we knew at that point we had won.

0:24:02 - (Alicia Pike): Word Valley is huge. That was really overwhelming the first time we drove through there before this meeting. It really kind of just blew me away. This grand, sweeping, creosote filled valley was just. It just felt so big. Just felt like you drop into this valley, and it's just unencumbered with human shit. It's just beautiful. And to think that there would have been a nuclear waste dump there is wildly inappropriate to scar wildlands like that and especially a water source. I mean, we have very few jobs as human beings, but not screwing up the water is kind of one of them, so. But not putting nuclear waste dump next to water seems common sense, but can't believe that was even a consideration.

0:24:57 - (Alicia Pike): It's just so big. Those little, tiny telephone poles or power poles just to me, I didn't even see them. Saw the immensity. There's the word I'm looking for. The immensity of how much nature is just around you.

0:25:14 - (Chris Clarke): I remain sorry that you didn't ever get a chance to meet Phil because I think you would have adored each other. I was really, really glad that we got to go out to Ward Valley together so that you could get a sense of the kind of landscape we were talking about. We went out in the company of our friend Matt Leivas, who we'll let introduce himself, but who is a very good friend of Phil's. We were out there also with Frasier Haney, who didn't say much while the recorder was running, but he was good company and did a bunch of the driving. And he is executive director of the Wildlands Conservancy.

0:25:54 - (Chris Clarke): Look him up in our show notes. It was very typical of doing anything involving Matt that we arrived to find. We expected to meet Matt out there at Ward Valley, and we arrived to find that he had made some friends just impromptu in the desert, including a couple, Jesse and Jessica, who were camping there on their way to Flagstaff, and their daughter Vivian. And Matt was absolutely thrilled by the fact that the baby girl there was named Vivian, because there was a Ward Valley activist named Vivian Jake, an elder in the Kaibab Paiute tribe, Vivian was a key figure there. So Matt just loved that. Whether you want to call it a coincidence or a signal from the universe or connection. A connection, yeah.

0:26:44 - (Alicia Pike): It felt very special. It was my first time seeing or experiencing any kind of Native American ritual. And we had just lost a friend in a fatal car accident the day before. So for me, you know, I'm here listening to the stories about Phil. I've never met him, but this morning ritual that he did for his friend, I mean, I began crying immediately. It was just what I needed that day. And I felt a great honor to be present and a great honor that he's allowing us to share that with the world.

0:27:19 - (Alicia Pike): There were definitely a slew of emotions going on there, but the most outstanding to me was that it was very clear that through teamwork and solidarity amongst fellows, it's possible to stop some really tragic actions from happening. It's pretty easy to feel all alone in the world, and, like, your voice doesn't really have an impact or an effect on anything, even your own life sometimes. But to meet up with a few of you that fought the good fight to protect Word Valley made me realize, you know, we're not alone in our feelings for wanting to protect the earth. And to see Matt just in tune, singing, making music with a rattle, you know, it just felt so natural. Everything.

0:28:19 - (Alicia Pike): He had the sage going, so you had the smoke, and you had the sound, and you had his voice, and it just. Everything just kind of made me feel, like, as hard as it seems, I almost feel like it's harder to not do something after experiencing something like that. You know, it feels like there's just not enough energy in a body to save a valley from the nuclear waste dump. But when you start making these connections with other people, some really good stuff can happen.

0:28:50 - (Alicia Pike): As depressing as the news is every day, it was just. It was really heartwarming to know that we're not alone and that to actually get on the scene with some people just made me feel an overwhelming amount of hope because something good can come of opposition to the greater tide.

0:29:11 - (Chris Clarke): Yeah, I think Phil would have really liked that. You got that?

0:29:15 - (Alicia Pike): Yeah. You guys are an inspiration. I mean, I was with my elders. I was besides Vivian, I felt like I was, you know, just a little newbie there who was just. Just learning the ropes of what's possible. And to see the three of you just friends, you know, you all have your respective contributions to the cause and that just there was an overwhelming sense of hope that came from that because you feel like the weight is on your shoulders, like you have to do something and you do, but it's not all on you.

0:29:49 - (Alicia Pike): And seeing you guys mourn the loss of a friend who helped fight that fight really made me realize the team effort. I don't know, it just, it makes me homesick for something I've never felt before today.

0:30:09 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): Ian Totua Ward Valley MA.

0:30:16 - (Chris Clarke): A sea.

0:30:16 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): Of Huito Here at Vord Valley, I'm singing a salt song or two for our dear lost friend Philip Klasky. Mover in a shaker helped us with this fight for 15 years against the Ward Valley and stopping his proposed low level radioactive waste dump here in California. And when we became friends, we didn't realize that we were going to become brothers, but we did a lot of love, respect, a lot of collaboration, a lot of discussion, a lot of laughs, some anger, a lot of joy at the end.

0:30:59 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): But Phil was the conduit that helped bring the tribes and all the other nations together in this fight. In his thesis an extreme and Solemn Relationship, he explains about the situation here at Ward Valley and we are very grateful for that. All the tribes. My name is Matthew Lavis Sr. I also go by Matthew Hanks Lavis Sr. Because of my grandfather Henry Hanks. He was the last chief of Chimwavies and I'm fulfilling that role as of the past 40 years and more so over the past two years.

0:31:41 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): But I'm from the Chinwavi Indian Reservation. I was born and raised in Parker, Arizona on the Colorado River Indian Reservation and moved to Chimwavia in 19 and got involved in desert protection since. And as a former chairman, I was involved during the day working with Phil and attorneys and developing the resolution that went all the way to D.C. and brought the five tribes together. Fort Mojave, Chimwebe Colorado, Ravinia Tribes, Quichan and Cocopah and formed the Five Nations Alliance.

0:32:14 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): That letter made an impact. We made our stand, we made our voices heard. But that bridge that was built was built not only by Phil, but a lot of others to come together to fight and combat this proposed dump 15 year fight, legal battle. Lot of travels to Washington D.C. to Sacramento, to Mexico City, all over Arizona and California. Explaining about Ward Valley and how sacred these lands are to the indigenous, that the tribes came together and protested and challenged the federal government in collaboration with all the different entities that were working together to stop this Ward Valley.

0:33:08 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): While Phil passed, his legacy will live on. He touched our hearts and our minds, and he got us to talk and collaborate and communicate. He was an excellent communicator, excellent journalist, and everybody who had read his work, so gonna miss his works. But we love Phil. Honor and respect, love to Phil Klasky, his family and all those help here at Ward Valley in this fight. Commemorate this day, May 11, for Klasky.

0:33:53 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): I'll sing these songs in Fork, Phil, and they're salt songs, but it's a song about the Riverside Mountain, the sacred mountain. And I'll go ahead and sing it for you all.

0:34:07 - (Chris Clarke): I need to break in here quickly with a note. The salt songs are a Paiute and Chemoevy cultural property. They're very important to the cultural survival of people associated with the Paiutes, such as the Chemoevi. And as such, I took pains to ask Matt, before recording, whether it was appropriate to record the salt songs that he was going to sing out there in ward Valley on May 11 or. And he assured me that it was fine.

0:34:29 - (Chris Clarke): As you will hear after the salt songs that he sang, he had a moment of intense emotion and listening to it afterwards. The next day, I called Matt and I said, I want to thank you for allowing us to record the salt songs you sang for Phil. I just wanted to ask you again just to make sure that it's okay to include them in the podcast. And he said, yes, absolutely, it's fine. And he said, actually, it's one salt song about Riverside Mountain in two parts.

0:34:58 - (Chris Clarke): One that's supposed to be sung in the evening, and the other is supposed to be sung the next morning. I asked whether it was a problem for people to listen to it on the podcast at the wrong time of day. And he said, since it was not a ceremonial singing, that that was not a problem. And then I said, you know, Matt, there was a moment after you were singing where you were really having some intense emotion there. And it seemed very private, and I'm inclined to omit that from the podcast, but I just wanted to see what you thought.

0:35:29 - (Chris Clarke): And he said, include it. The purpose of these songs is to bring out the emotion that you have locked inside. And he reminded me that the Chemoevi, traditionally, when they have lost someone that's close to them, they have a ritual cry in which they catharse and they try to heal a little bit. And he said, so, yeah, run a snippet of it. I said, well, it's 45 seconds long at most. Probably more like 30.

0:35:55 - (Chris Clarke): And he said, yeah, run the whole thing. And I'm saying all this prior to sharing with you the salt songs he shared with us just out of an abundance of sensitivity to concerns about appropriation, about invasion of privacy, about cultural respect. Anyway, back to Ward Valley.

0:36:17 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): Hey, we water thorny way oh, we water thorny o tonight hey, we water Riverside mountains Sacred mountain we want a Sony we want a tonight we want a toning Phil is gone. Took that bridge across the Milky Way to be with his family and creator, all his loved ones. Our love. Phil to you, to all the people who fought Ward Valley. This is your land. All of you all. No matter what race, what color Mother Earth, Living, breathing.

0:39:04 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): I say that now from my heart. My lost brother and to all the friends who loved him. Miss you, Phil. God bless Ma. Ma. Thank good man, Nakamut. Strong. Naksapet Nakbutsuan. He knew. He knew our people. He knew our culture. He was learning. We were sharing with him. We even gave him a name. Wampiquets for the Scorpion. And his favorite place, Wonder Valley. Ma. May Wonder Valley always be Wonder Valley.

0:40:14 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): Thanks to Phil, loved ones and our brothers and sisters. All of God's creations. Ma Long. Good night. You said Ma. Thank you. Thank you for being here.

0:40:38 - (Chris Clarke): Thank you.

0:40:39 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): Good day.

0:40:40 - (Alicia Pike): Thanks for including us.

0:40:41 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): But the river. The river is the lifeblood. It's like the veins in our arms. I seen you at a kayak. I'm encouraged to come over to the lake and see this river where I'm taking them, because the microcosm of the Gulf of California. Difference is the water is flowing here. Down there, it is not. It doesn't reach its full destination. It's like in our veins, our blood circles, recycle, goes through, cleanses itself, refreshes, energizes, nourishes us.

0:41:15 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): That Colorado river is just like a vein in the arm. Whole Mother Earth being clogged up its arteries with all this plaque and sediment from debris floating down. And it's not purging and scouring itself like it's intended to do. It's like our blood runs through. It has to be filtered out before it gets to the ocean. Well, everything's been disrupted because of the dams. Creation of dams and hydroelectric power and total disregard for proper management of the river.

0:41:46 - (Matthew Leivas Sr.): Just as the mismanagement of Mother Earth and what BLM has done with Western thinking and science and not thinking about communicating. And that's the key is communication. I think we found that all out here at Ward Valley. Communication is key to this, these types of fights. That's what Phil brought, that collaboration for all of us. I'm really grateful for being here.

0:42:12 - (Chris Clarke): So again, it comes down to this. Pay attention to yourself, breathing in and breathing out. Take the desert ecosystem into yourself. Accept the gift of the oxygen that the desert provides, and then give up some of yourself to the desert to feed the plants that form the base of the food chain. You are part of the desert ecosystem. You are a part of the desert that has grown aware of itself and that can act on the desert's behalf to defend it.

0:42:45 - (Chris Clarke): If you think of yourself as alone, the threats to the desert may seem insurmountable and catastrophic. But when we work together across all the real and arbitrary and imaginary and exaggerated lines that we as human people use to separate ourselves from one another, we can accomplish great things while we still breathe. Those who have gone before, like my friend Phil Klasky, have done the work that they could do, and now they leave it to us.

0:43:17 - (Chris Clarke): I just ask, now that you have learned or have been reminded that you are one part of the desert's immune system, what do you do next? This one's for you, Phil. Thanks for everything.

0:43:37 - Bouse Parker: This episode of 90 Miles from Needles was produced by Alicia Pike and Chris Clarke. Editing by Chris podcast artwork by our good friend Martin Mancha. Theme music is by Bright side Studio. Other music by Nuclear Metal, Luca Francini and Orchestralis. Thanks to Envato. Follow us on Twitter, Instagram, Instagram at my From Needles and on facebook@facebook.com 90 miles from needles listen to us at 90miles from needles.com or wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you to the Mojave Project and Kim Stringfellow for kindly allowing the use of their recording of Phil Klasky. The Mojave Project is a transmedia documentary and curatorial project exploring the physical, geological and cultural natural landscape of the Mojave Desert. Visit Mojaveproject.org to see more of this compelling project.

0:44:28 - Bouse Parker: Audio of Senator Frank Murkowski via C Span. Our deepest gratitude to Matthew Hanks Leyvas Mawk means thank you in the Chemehuevi language. Thanks to our newest Patreon supporters, Chuck George T. Arch McCullough and Cameron Meyer support this podcast by visiting us at 9zero miles from needles.com and making a monthly pledge of as little as five bucks. Our Patreon supporters enjoy privileges including early access to this episode and an exclusive Joshua Tree National park campout in September 2022.

0:45:02 - Bouse Parker: Crucial support for this podcast came from Tad Coffin and Lara Roselle. All characters on this podcast who have lived here longest and know best are least conspicuous. The oldest mountains are lowest, and the scorpion sleeps all day beneath a broken stone. This is Baus Parker reminding you to call your friends. See you next time.

0:45:56 - (Chris Clarke): Sit, heart, sit. Good dog.

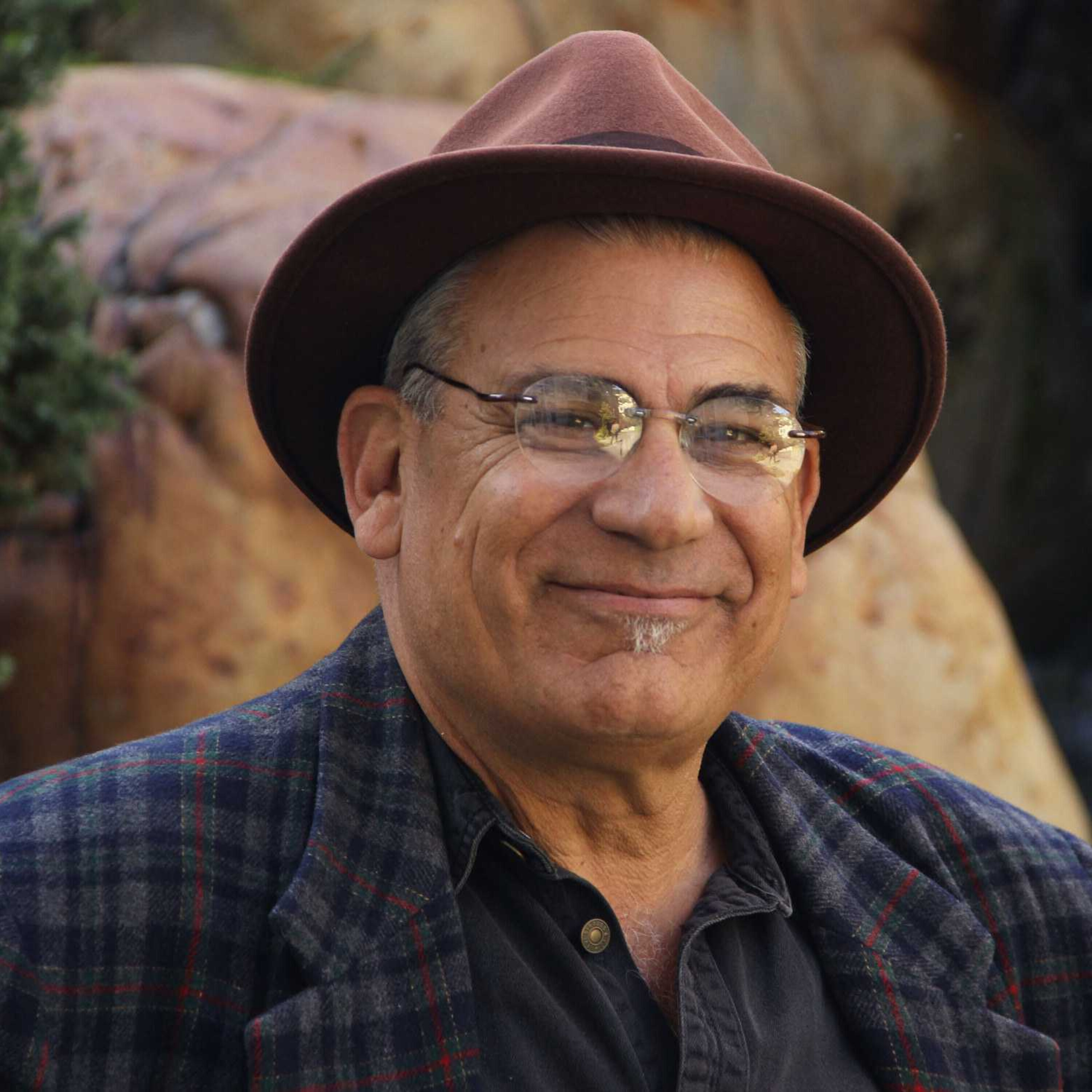

Matthew Leivas is a respected Chemehuevi elder, Salt Song singer, tribal scholar and environmental activist. His detailed and comprehensive knowledge of his people’s history, culture and the landscape they inhabit—along with the varied, complex issues affecting contemporary Chemehuevi people—is most impressive. Leivas was born and raised at Hanks Village, an Indian allotment in the Parker Valley at the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) reservation.