Episode Summary:

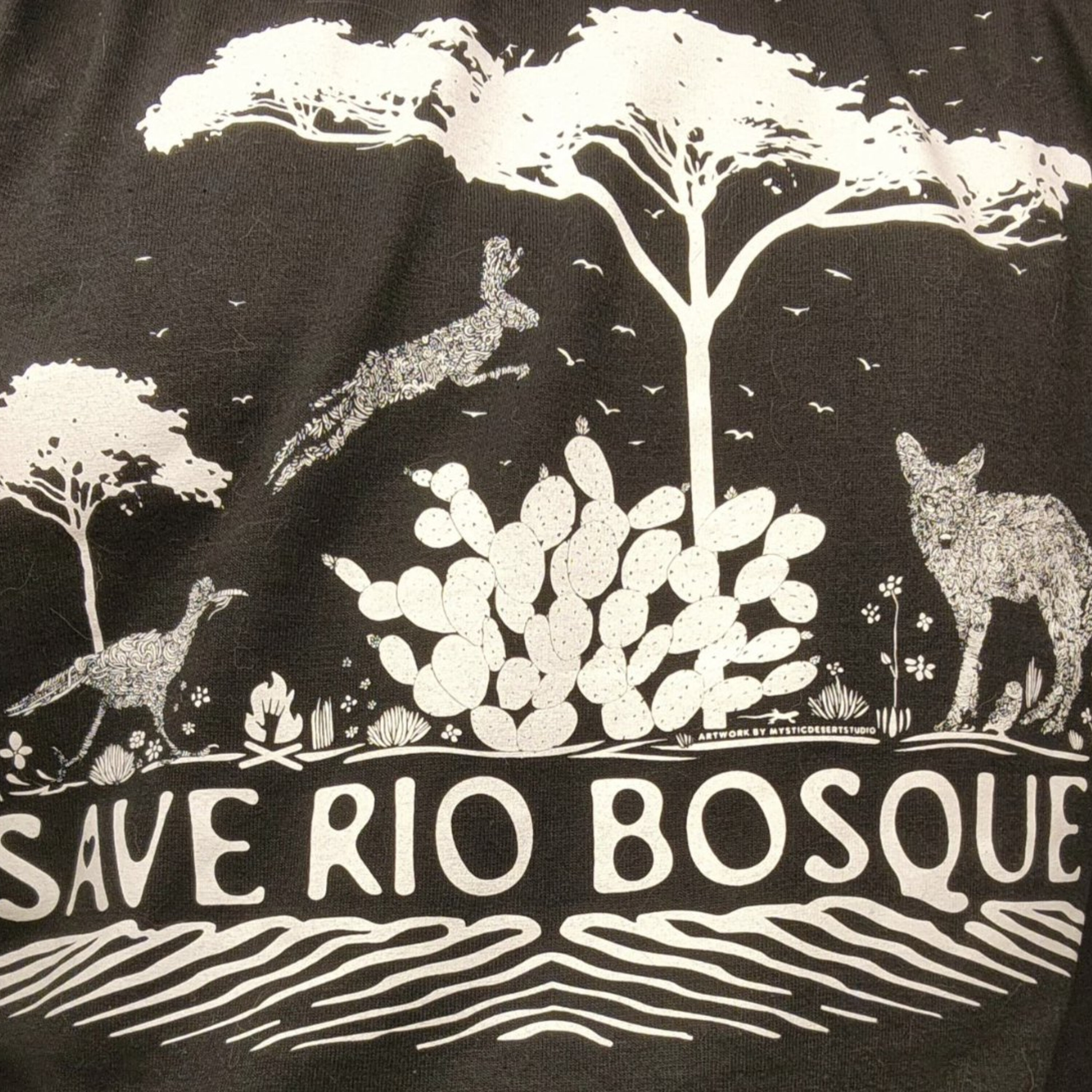

In this thought-provoking episode of "90 Miles from Needles," host Chris Clarke engages with Jon Rezendes to explore the rich ecological landscape and current environmental threats facing the Chihuahuan Desert, particularly the battle over the Rio Bosque wetlands in El Paso. The conversation provides an in-depth look at the socio-political challenges and the community's fight to prevent detrimental changes.

Jon Rezendes passionately discusses the significance of protecting the delicate Rio Bosque wetlands against proposed infrastructure projects such as a disruptive highway. The area, crucial for migratory birds and local flora and fauna, faces the pressure of urban sprawl and industrial traffic which could irrevocably damage this unique ecosystem. Supported by the local community and organizations, Rezendes highlights the urgent need for advocacy and action to sustain this natural gem. He envisions a future where rewilding efforts expand, forever changing the local desert into a cradle of biodiversity that could one day welcome apex predators like the Mexican wolf back into the region.

Key Takeaways:

- The Rio Bosque wetlands near El Paso are a vital habitat for over 260 bird species and numerous other animals, yet they are currently endangered by various threats, including proposed highway projects.

- Jon Rezendes advocates for realistic and sustainable alternatives to alleviate traffic that don't damage vital ecosystems, such as improving the existing rail transit system.

- Defenders of the wetland are rallying against Texas DOT's proposal for highway construction, gathering community support through petitions and local agency involvement.

- The vision for the Rio Grande Valley is one of expanded rewilding, potentially re-establishing apex predators like the Mexican wolf and removing barriers such as the border wall for ecological restoration.

- It's critical for the conservation community and influencers beyond Texas to support the efforts to protect and rewild the Chihuahuan Desert ecosystems.

Notable Quotes:

- "We intend to shine enough light on this situation to make sure that we're elevating the voices of the people in Socorro that don't want their home to be turned into an unrecognizable industrial wasteland."

- "El Paso is small in terms of our influence, but we are mighty in terms of our grassroots efforts."

- "We are not going to let this happen. This is absolutely backwards, and we will do anything in our power to prevent a highway through our wetland."

- "Nothing would make me happier to know that wolves are running up and down the Rio Grande Valley again, passing between Mexico and the United States."

- "Rio Bosque is fighting for survival amid Texas' broader environmental narrative, where prosperous future melds with respect for the land and vibrant riparian forests."

Resources:

- Follow Friends of the Rio Bosque on Instagram:@friendsriobosquewetlands

- Comment on the Border East highway before May 14 (Even if you're not a Texan).

- Texas Lobo Coalition: Texas Lobo Coalition

As we delve into the rich tapestry of environmental activism and the future of the Chihuahuan Desert, we invite listeners to experience the full episode as Jon Rezendes shares his urgent advocacy call for Rio Bosque wetlands. Tune in and join this engaging conversation that may very well shape the natural legacy of Texas and beyond. Stay connected for more episodes from "90 Miles from Needles" that continue to enlighten and inspire.

Become a desert defender!: https://90milesfromneedles.com/donate

See omnystudio.com/listener for privacy information.

Like this episode? Leave a review!

Check out our desert bookstore, buy some podcast merch, or check out our nonprofit mothership, the Desert Advocacy Media Network!

UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT

0:00:00 - (Chris Clarke): This podcast is made possible by financial support from our listeners. If you're not supporting us yet, check out nine 0 mile from needles.com. Donate or text the word needles to 53555.

0:00:24 - (Joe Geoffrey): Think the deserts are barren wastelands? Think again. It's time for 90 miles from needles, the Desert Protection podcast.

0:00:43 - (Chris Clarke) Thank you, Joe Geoffrey, and welcome to another episode of 90 Miles from the Desert Protection podcast.

0:00:50 - (Chris Clarke): I'm your host, Chris Clarke, and we are talking about the chihuahuan desert today.

0:00:54 - (Chris Clarke): You know, I'm really fond of the.

0:00:56 - (Chris Clarke): Chihuahuan desert, and I couldn't have said that last year because I didn't know the place at all. Now I only know it a little.

0:01:02 - (Chris Clarke): Bit, having spent a couple of weeks.

0:01:03 - (Chris Clarke): There earlier this year. And El Paso is an especially interesting place. It has a really familiar vibe to me. For one thing, I spent a lot of my life living in places like Buffalo, New York, and Oakland, California, and just the sort of working class realism that those two cities at least used to have when I lived there. Oakland has changed a bit, but that working class vibe is definitely something you can find in El Paso.

0:01:30 - (Chris Clarke): And it's also just in a beautiful place surrounded by the Sierra Juarez and the Franklin Mountains, not far from the Oregon Mountains in New Mexico. And so I've come away from my extremely brief sojourn in El Paso this year quite impressed with what's going on there. I mean, there is sprawl, for sure, but there's also a core of interesting, walkable neighborhoods. There's a top notch university there that has greatly improved the lives of people that live in El Paso. And there's also a growing and extremely enthusiastic group of people in the city who want to defend the environment, whether that's the Franklin Mountain State park, the Castner Range National Monument, which was established last year, or even smaller places. An episode or two ago, I mentioned briefly in passing the campaign to save a wetland near El Paso that's right on the border, right on the Rio Grande, called Rio Bosque wetlands. The Rio bosque wetlands are threatened by a couple of different things, including big existential problems like sprawl and industrial traffic from the border crossings based on our trade policy, not to mention infrastructure for the border wall, but in particular, a proposed highway project that poses a serious threat to this nearly 400 acre wetland right on the border. And there's a thriving campaign to fight this highway to protect that wetland. Over the weekend, I talked to John Resendis, who's been one of the central people trying to rally support for the Rio Bosque wetland and getting some great results, making some amazing progress. I think you'll find our conversation really interesting.

0:03:06 - (Chris Clarke): But first, if you're a fan of 90 miles from needles, you probably know by now that it is made possible by listeners just like you. We do not get grants or advertising revenue or foundation funding at the moment we are looking into all those sources of income, but right now this is all supported by relatively small donations from listeners just like you, five or ten or $20 a month. If you want to join the group of people that's been making these episodes of 90 miles from needles possible, you can go to 90 milesfromneedles.com

0:03:42 - (Chris Clarke): donate to find a couple of easy ways to toss us some cash. We would really appreciate you helping us cover some of our expenses, as would your fellow listeners. And along those lines, the Mazamar Art pottery studio, which is in Pioneer Town, California, not too far from 90 miles from needles, world hq is putting together a summer group show focusing on the issue of preserving the dark night skies in the desert. This is a pottery studio, but all media that are appropriate for an outdoor exhibit are welcome.

0:04:18 - (Chris Clarke): The deadline for submissions is June 10, 2024, and this is where 90 miles from needles gets involved. Mazamar Art pottery has decided to ask for a small donation per participant, optional, but definitely encouraged, and that money will be donated to support 90 miles from needles and the desert advocacy media network. We are incredibly grateful for that show of support. I will be there at the opening on June 15 in Pioneer Town on Main Street m a n E street.

0:04:51 - (Chris Clarke): Again, like I said, the deadline for submissions is June 10. You can email info@mazamar.com to participate, or check out Mazamar's instagram feed at Mazamar art pottery. Good folks. They definitely deserve your support. They've been very supportive of this podcast and we are really touched that they have included us in this event. And so, with no further ado, let's get to our interview with John Resendis of Frontera Land alliance and a number of other organizations in El Paso.

0:05:30 - (Chris Clarke): I found our wide ranging conversation gratifying, and I think you might too.

0:06:06 - (Chris Clarke): John, thanks for joining us at 90 miles from Needles, the Desert Protection podcast. Do you want to tell our listeners who you are?

0:06:13 - (Jon Rezendes): Awesome. Thank you, Chris for having me. My name is John Rosendez. In a formal capacity, I am the vice president of the Frontetta Land alliance who janae Gotien Rocio. They were guests on your podcast a few months ago, but today most of my comments are just going to be as myself, private citizen. I was born and raised in southeastern Massachusetts in a small coastal city called Fall River, and I'd never been to the desert until the army had brought me to the desert in various capacities, Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, and then ultimately when I was assigned as a company commander to Fort Bliss, Texas, which is in far west Texas, in El Paso. Can't get any further west in Texas than El Paso and El Paso county right here in the heart of the northern chihuahuan desert. And I consider myself an Ackerman. El Paso in like the late Judy Ackerman, in that the army brought me to El Paso, but the mountains kept me here.

0:07:00 - (Chris Clarke): I'll say, as a quick parenthetical note that Judith Ackerman was an El Paso based conservationist who sadly died of cancer in 2022 and November 6, 2022. In addition to working to establish Castner Range National Monument in the Franklin Mountains, Ackerman was also a staunch defender of Rio Bosque, to the point where she chained herself to a bulldozer at the wetlands park. In 2008 to protest the building of the border wall. She campaigned against the Texas DOT's plans to widen Interstate 10 in downtown El Paso, founded the Viejitas for Choice Network to work for reproductive health rights.

0:07:39 - (Chris Clarke): She was a frequent commenter at El Paso city council meetings. She was a voting rights advocate. She registered thousands of El Pasoans to vote. Definitely someone worth emulating. Back to Jon.

0:07:51 - (Jon Rezendes): It is an absolutely beautiful gem of a city for those that have not been. It's a city of about three quarters of a million people that rings the Franklin Mountains, which is protected both as a state park and as Castner Range national monument. But it also, of course, is a sister city with Ciudad Juarez just across the Rio Grande or the Rio Bravo. And it really is a binational community. It is the largest set of cities on the border.

0:08:16 - (Jon Rezendes): And truly, I interact with people from Juarez every single day. And this idea that we are two cities is, in my opinion, purely a fabrication of the line on the ground drawn by the river. And speaking of the river, we recently had an incident here where we have this beautiful 372 acre rewilded wetland that just celebrated its 50 year anniversary. It's called the Rio Bosque Wetlands park. And again, it is just a bosque means woodland, and obviously Rio means river. So this is the riparian forests that used to exist all up and down the Rio Grande corridor that looked very much like maybe the Gila river or many of these other rivers that were just lush and green and covered in cottonwoods and native vegetation.

0:08:56 - (Jon Rezendes): As most of your listeners know, the Chihuahuan desert, the Sonoran desert. Those were the only places in the north american continent that you could find all five of North America's large carnivores. You found the grizzly bear, the black bear, the jaguar, the Lobo, and the mountain lion. And these riparian corridors were the corridors that all of our large animals and indigenous peoples thrived upon in our deserts. From west Texas through New Mexico, Arizona, into California, and of course, into Sonora and Chihuahua and Coahuila. It was a very lush and verdant environment, and the community came together about 50 years ago to rewild this wetland. Very special little place.

0:09:34 - (Chris Clarke): I'm assuming that there's mesquite and some other legume trees growing in the bosque there, but I haven't seen the place. I missed it on my visit to El Paso this year.

0:09:43 - (Jon Rezendes): It's 372 acres along the Rio Grande that generally runs from northwest to southeast. There are a number of canals that water is provided to the bosque by El Paso, water from the Bustamante wastewater treatment facility. So it is a collaborative effort in this relatively urban environment to bring water back to the desert to recharge our aquifer. And there's about 9 miles of trails that wind through these 372 acres and two very large wetland cells.

0:10:11 - (Jon Rezendes): And these wetland cells are a haven for birds of all types, but in particular, migratory birds. There have been over 260 species of birds documented there. That is a significant stop on the midcontinent flyway for birds that are maybe going up to the Bosca de la Pache, further up the Rio, or maybe they're making the long trek up from Central America. One bird in particular that is seen very often at the Bosca is the Swainsons hawk.

0:10:35 - (Jon Rezendes): I have a personal campaign to call it the Hornada hawk. Hornada means journey in Spanish, and I personally believe that, like the American Ornithological Society has said, we should be in the process of renaming any animal that is named after a human being. So that's just a little plug for the hornadahawk. But these amazing trans equatorial migratory birds come all the way up from Argentina to our desert here, and you can find them nesting at the Bosca.

0:10:58 - (Jon Rezendes): And they are constantly circling overhead with their beautiful white t shaped bodies and their brown wings and brown capes. But again, that's just one of the many species. Any time that you go to the bosca, you can probably see stilts or fallow ropes or sandpipers or ibis or kingfishers. Heron of multiple varieties. Egrets. It is truly a miracle in the desert that many people came together to make a reality. You walk through the mesquite and the Huizache and the Mimosa and the cottonwood trees that are being painstakingly restored, and it really. It is like a modern miracle, because as you drive into the bosque, you actually drive through a very major industrialized area in El Paso's lower valley. And the face of the lower valley is changing quite a bit from the time when the Piro and Manso and Apache and Pueblo people lived along those riparian forests to even just 300 years later, many of them have been cleared for. First it was farms and ranches, and then it was industrial activity.

0:11:57 - (Jon Rezendes): And there are numerous ports of entry that dot the river. There's actually one major port of entry just a mile or so north of the bosque there itself. So to have this gem of a rewilded wetland in the desert amidst all of this development and chaos, it's truly special. And it is one of the last remaining windows into that natural history in El Paso county and in the northern chihuahuan desert.

0:12:20 - (Chris Clarke): It sounds like it's a good thing that you all have this place protected in perpetuity, right? Or am I missing something here?

0:12:27 - (Jon Rezendes): Yes, there are numerous threats that the Rio Bosque is facing right now. The first one that I'd like to talk about is, for those of you that don't know, El Paso. El Paso is in Texas, but El Paso is not like Texas. We basically don't show up on anybody's maps. Folks in Austin hardly ever consider us. We are the forgotten child of Texas. We are essentially New Mexico's largest city, and a lot of people don't understand that Austin and Texas, in their extremely limited wisdom, push sledgehammer type of solutions, when really all we need is a screwdriver.

0:13:00 - (Jon Rezendes): So what's going on with the bosque right now is with that development that I had mentioned that's lining the lower valley in the development that is honestly going on everywhere in the west. Despite our water struggles, the Texas Department of Transportation recently revived an old study for an expansion. They call it the border Highway east study. And all three alternatives that they've planned, which are basically just lines drawn on the map from Austin, would pass directly through the Rio Bosque Wetlands park.

0:13:27 - (Jon Rezendes): One of the alternatives, alternative three, is the most particularly devastating, where the highway, in an elevated form, would go over both wetland cells, functionally killing the wetland. You can imagine moving the concrete and cement and rebar and equipment and trailers and people even just to initiate construction. Never mind to conduct the construction and then establishing a new normal of a six lane highway passing directly over a fragile desert wetland.

0:13:53 - (Jon Rezendes): It's honestly one of the dumbest ideas I've heard in my 37 years on earth. Whereas the other two alternatives go directly over, there's a canal that kind of boxes the Boscayin, and this canal provides water further down the river to farmers on the US side of the border. The highway would pass directly over this canal, and a riparian forest that is purely a buffer right now has no protection. It is owned by the El Paso Water Public Service Board, and they are planning for it to be a carbon sink.

0:14:21 - (Jon Rezendes): And alternatives one and two would pass over this canal, over the northeastern edge of the bosque, and he would put a spaghetti bowl interchange directly on top of the visitor center. Absolutely wiping out those riparian forests in the eastern section of the bosque and destroying all the hard work that people have put in for this wetland. There are several man made burrowing owl nests around the bosque, I'd say maybe a half a dozen or so.

0:14:47 - (Jon Rezendes): They are very lovingly maintained by the El Paso urban wildlife biologist, Lois Balin, the friends of the Rio bosque, by the park manager John Sproul, and assistant manager Sergio Samaniego. They lovingly maintain this wetland, these burrows, this wildlife, this open space for the people of the lower valley. And there are a number of threatened species that are either resident at the bosque there or are transient in their migration.

0:15:11 - (Jon Rezendes): There is no permanent protection for the bosque at this point, but that is something that we as citizens of El Paso are pushing our elected officials for, especially as folks from 800 miles to our east are trying to put a highway through our wetlands.

0:15:25 - (Chris Clarke): So where does the project stand at this point?

0:15:27 - (Jon Rezendes): There are environmental studies yet to be conducted. They did an initial environmental study. So actually, this plan to extend the border highway is about ten years old, but it had been put down before, and they're trying to re revive it based upon noise that some landowners that are looking to profit off of their land in the lower valley are pushing for some of this. So as these loud and rich voices are pushing for a highway to again, profit off of this, the TxDOT revived it. There was an initial environmental study done. I will say that it is not very thorough.

0:16:02 - (Jon Rezendes): Again, I'm not an environmental professional, but when you read the environmental study that was initially done ten years prior, there's no mention of this rewilded wetland. There's no talk of these burrowing owl resident nests. There's no talk of the 260 species of birds that have been spotted there. There's no talk of the beaver that lives there and makes his dam. And we actually, not we, but the friends of the Rio Bosco actually installed beaver deceivers so that our one resident beaver can feel productive, but the pipes beneath his dam can allow the water to pass.

0:16:31 - (Jon Rezendes): That's just a side tangent. But again, the initial environmental study was very limited. It made it sound like it was just dust and mesquite coppice dunes, when in reality it is a thriving riparian forest with a great abundance and diversity of plant life and wildlife. We are still early. It still is in the study phase. No money has been allocated based upon the way that the Texas Department of Transportation and their contractors were speaking to those of us who attended the open houses on May 1 and May 2.

0:17:03 - (Jon Rezendes): They are actively lobbying for this rather than just listening to our concerns and listening to the voice of the community. It was very clear that there was an active push by the powers that be with money and influence to make these massive plans to host these open houses, to hire these dozens of contractors, that there are forces east of here that want this to happen. But fortunately, the community is coming together in a very strong way to protect the bosque.

0:17:31 - (Jon Rezendes): We had about 2000 signatures in less than a week on our petition. We had hundreds and hundreds of people show up to these open houses on May 1 and May 2 to make their voices heard. And we still have an open comment period until May 16, where folks can go on the Texas Department of Transportation website. There's information there under the border Highway east study, where there's a phone number they can call or an email that they can reach out to to make their voice heard as well. And you can use that line as many times as you want. You don't have to be a Texas resident to make yourself voice heard that a highway through a wetland is a really bad idea.

0:18:07 - (Chris Clarke): And we will definitely link to that website in our show notes so that people can weigh in. You mentioned three alternatives, none of which are great for Rio Bosque. Is there an alternative that's undescribed, that defenders of the wetland park would prefer? Or is it a no action kind of thing that would work best?

0:18:29 - (Jon Rezendes): Well, when it comes to the highway, it's clearly option four. No highway. There's a lot of historic buildings, the mission trail, 50 zero year old spanish missions. And again, we can say whatever we want about the history of the Spanish and the promotion of catholicism on the indigenous peoples and the violence that happened. But that is still history. That is still history that needs to be preserved. There are still thousands and thousands of working class people that live in those neighborhoods that are having these decisions made for them by outsiders.

0:18:58 - (Jon Rezendes): So we still have time to act and to speak because it is early enough in the process, and we will do so. There is an alternative to alleviate traffic in the lower valley. If the lower valley is going to be developed in the way that the powers that be are looking to push said development, rezoning a lot of this land, from farm and ranch to industrial, that is another threat that faces the bosque. But there is an alternative that is realistic and that is achievable, and that will cost less than the $1.8 billion that they're proposing for this 20 miles highway.

0:19:30 - (Jon Rezendes): The reason the traffic in Socorro is so bad is because there is a surface rail that goes all the way from downtown, all the way down the lower valley, that is constantly putting cargo trains and freight trains double decker stacked on the surface. That is causing hour long delays up and down these north south running roads that are preventing people from having real mobility, because these are 300 freight car long trains at some point, shipping freight all up and down the Rio Grande.

0:19:59 - (Jon Rezendes): And none of the roads in Socorro or the lower valley pass over the rail. Or alternatively, the rail has not been elevated to allow the roads to go underneath the rail. So one of the major reasons for this traffic is because people are sitting at these railroad crossings, and they're pushing more and more people down this direction. So all they're doing in this idea of with the highway is pushing even more and more traffic to the fertile valley. More and more traffic towards the water and the wetlands and the farms and ranches that are still extant there that haven't already been taken over by development.

0:20:30 - (Jon Rezendes): So what we have proposed, and I'm not a civil or mechanical engineer, and I'm not a city planner, but it makes perfect sense to me that it's been done in many other places, including where I'm from in southeastern Massachusetts, which historically was overlooked. It was flyover country for a lot of New Yorkers trying to get to Cape Cod. They're building a light commuter rail to connect these communities of the south coast to Boston. They're doing the same thing in Houston with light rail. There are communities all around the country that are starting to ditch highways and embrace the idea of public transit based on rail.

0:21:05 - (Jon Rezendes): It gives people an alternative. It doesn't stop people from using highways. It doesn't take cars out of homes, but it gives people a realistic alternative to get to downtown. To get to uptown and the University of Texas at El Paso. And people in the lower valley don't have these options right now. All they have are their cars and their trucks and their surface roads and their railroad crossings and the one loop highway that they have. And they don't have any options or alternatives. And I think it would be a lot smarter, more sustainably oriented, and more 21st century aligned for TxDOT, who also manages the rail, to actually think outside the box.

0:21:40 - (Jon Rezendes): And again, rather than bring a sledgehammer from Austin when we have a screwdriver problem, to actually look at fixing the rail.

0:21:47 - (Chris Clarke): That's fascinating. Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. And it is surprising that that didn't make it into the official list of alternatives just because it seems like the freight rail is just such an obvious problem.

0:21:59 - (Jon Rezendes): The other thing, too, Chris, is that there's a lot of money that is pushing this. The trucking industries, the ports of entry. There's a lot of industrial traffic that comes up from Mexico. Juarez is one of the biggest manufacturing cities in the world. So we have a ton of traffic. There are many ports of entry. These ports of entry are all gridlocked because of the new inspections that have come down on both sides of the border. It's really crushing our air pollution.

0:22:22 - (Jon Rezendes): And we're not looking at other alternatives. We're just listening to the trucking industry and the shippers and the manufacturers, and they're going, it's taking too long to get our goods over the border. Make us another highway. And these other folks that own industrial land near some of these other ports of entry that might not have as much traffic are saying, yes, build us a highway so that we can connect all these ports of entry so all these trucks and all these goods can go everywhere.

0:22:44 - (Jon Rezendes): And it's not citizens, it's not locals, it's not people that are conscious of this problem. It's money and goods and crony capitalism that's pushing this.

0:22:53 - (Chris Clarke): Right.

0:22:54 - (Chris Clarke): How are you feeling about the odds of success on your side, especially when you pull in the dynamics of global trade and demands of late stage capitalism, etcetera? It can sometimes seem like David versus Goliath, except David's got his hands tied behind his back.

0:23:09 - (Jon Rezendes): Understood. Understood. You know, what I think has been great is I will say that on Friday morning, after the second of the TxDOT open houses, the El Paso water came out and said that they are opposed to all three options. Back in April, I had gone before the El Paso Water public service Board and pleaded my case. That's actually the moment that went viral, is those videos of me in front of the El Paso Water Public Service Board went locally viral here in El Paso on instagram with 17 or 18,000 likes, hundreds of thousands of views, and a lot of people were in an outrage.

0:23:42 - (Jon Rezendes): And that outrage has pushed the El Paso water to actually take a look at this and go, you're right, this doesn't make any sense. It would decrease our security. It would increase the risk of our operations. El Paso water could potentially be in violation of the Texas Commission of environmental quality based upon the impacts of the construction. And then they actually stepped up and did the right thing. They said that we are part of the stewardship arrangement for the Rio Bosque wetlands, and all three options would prevent that stewardship of said land. To have the El Paso water department come out and publicly make that statement, that was a huge boost for us.

0:24:15 - (Jon Rezendes): And I will say that definitely boosted our confidence. But, Chris, we're not going to lose. We're not going to let this happen. This is absolutely backwards, and we will do anything in our power. Judy Ackerman was arrested in 2008 protesting the border wall. And obviously, the border wall was a much bigger, different issue than just a highway. We can absolutely defeat this highway. We're not going to let it get built.

0:24:37 - (Jon Rezendes): Yeah.

0:24:38 - (Chris Clarke): Just as a side note, I'm really regretting that I started making friends in El Paso too late to have gotten to know Judy. She seemed like a force of nature, unbelievable human being.

0:24:48 - (Jon Rezendes): She was my inspiration, and I only met her a few times. I didn't know her very well, but her story and the impact that she had on me just in a few times that I met her as a veteran, as a retired sergeant major, as somebody who knew how to use their voice and knew how to elevate the voices of others. She's a real inspiration. And the entire conservation community should know the name Judy Ackerman. Yep.

0:25:09 - (Chris Clarke): We'll see what we can do. You mentioned other threats to Rio Bosque wetland.

0:25:15 - (Jon Rezendes): Yes. There is a. So this is a bit of a complex and political issue here. There is a concrete mixing facility that I recently toured that is just to the north of the bosque along that northeastern canal that I was describing to you. It has been operating for a few years now. It's operated by job materials. And job was allowed to build this concrete mixing facility on this land that was zoned farm and ranch land, which anyone who knows anything about property values in this area understands that farm and ranch land carries about one 10th the value of industrial land. You're talking about $4,000 an acre versus $40,000 an acre. And job has a lease on this land, a ten year lease. And he's allowed to do only public works with the concrete that he makes at this facility.

0:26:03 - (Jon Rezendes): So, for example, the Bustamante wastewater treatment facility that EP water runs, that is by the bosque, that provides the wastewater to the bosque to be naturally filtered by the wetland and returned to the aquifer, which is a brilliant idea. But job provides concrete to that facility, to the ports of entry that are nearby, because concrete only has a 30 to 60 minutes shelf life stability. So job needs to have these mixing facilities strategically placed.

0:26:28 - (Jon Rezendes): And in his words, concrete is a commodity. So he views this concrete as a commodity. What is happening is that he has asked the city council, and Stanley job is very influential, to rezone this farm and ranch land into industrial land. So about ten acres that he's on right now with his one concrete mixing hopper. And he wants to turn into industrial land so he can serve the commercial entities that are on the other land around him.

0:26:53 - (Jon Rezendes): The problem is that without talking about the environmental impacts of concrete, concrete is not as bad as cement. I think that's cement is one of the worst environmental things that you can do to communities. His concrete is not as bad. He's not burning anything there. His effluent does go into a slag pond out back, which is not great, because that slag water is getting into our aquifer. But he is not dumping it into the canal. That's going to the bosque. So that is.

0:27:16 - (Jon Rezendes): So his impacts are on a scale of highway to natural state. He's certainly not on the highway end of the spectrum. He's about in the middle. But the precedent would be that, one, all of that land around there could then be justified as rezoned to industrial, because now he has the ability to serve concrete easily and readily to those other lands that are not in large use over there. Two is, it's still crony capitalism, it's still a non competitive situation where he's essentially gifted a ten year lease on that land at the previous rate because he already makes concrete for the public works and for the city.

0:27:52 - (Jon Rezendes): He's already got the contract. Just throw him a bone and let him make concrete for everybody else, and everybody profits, right? It's a non competitive environment that is the opposite of the way that capitalism is supposed to function. That is crony capitalism, and it is convenience for the city and for job. And it's just not the way that America is supposed to work. And then finally, again, it's the precedent with the rezoning of that land around the bosque, with the idea that we can just willy nilly turn farm and ranch land into industrial land without considering the impact to the people, without considering the traffic, without considering the air pollution, the noise pollution, and the health impacts. This is a dangerous precedent that would be set.

0:28:29 - (Jon Rezendes): That would be, again, not the existential death of the wetlands that the highway would provide, but it would be maybe one of the first of death by a thousand cuts, by essentially turning that area into an unrecognizable industrial wasteland.

0:28:43 - (Chris Clarke): So is there a hook that activists have at this point, or is this right now in watch and monitor mode?

0:28:51 - (Jon Rezendes): On May 7, the city council is supposed to be voting on this rezoning to allow the land to be permanently industrial, which would then allow job to sell his concrete wares to the other industrial operators down there. We've organized a campaign to educate and speak. We've encouraged everyone to sign up for the city council session on Tuesday, May 7. And I'll make sure to get you that information as well, Chris. But it's just. It's small time politics in a city of nearly a million people, and you can't get away with this kind of stuff when there's enough eyes on it.

0:29:23 - (Jon Rezendes): And we intend to shine enough light on this situation to make sure that we're elevating the voices of the people in Socorro that don't want their home. That was once again the mission trail and beautiful cottonwood, riparian forests and small family farms. It is now being covered in giant industrial facilities proximate to the port of entry, so that the fat cats can get richer again. This is another situation where the voices of the community are not being heard.

0:29:51 - (Jon Rezendes): In order to curry favor with city councilors and local power brokers and these backdoor deals that need to have light Shone upon them,

0:29:59 - (Chris Clarke): What can people outside Texas do in general to help you guys out? Are there websites you want to direct folks to, or is there a way to plug in non locals that you guys have crafted?

0:30:14 - (Jon Rezendes): Yes. So that is, I would encourage everyone. I know not everyone is on Instagram, but at this point, Instagram is one of the best places for non filtered news, where you're getting it directly from the source rather than it passing through the bucks of major media. So if you would follow the friends of the Rio Bosque Instagram page, their Facebook page, if you go to their website, that is one of the best places to get all of the latest news.

0:30:36 - (Jon Rezendes): If, even if you don't live in Texas, I encourage you to make comments on the TxDOT website or email or phone line, which I'll make sure that we have artifacts for Chris, because you don't have to be a Texas resident to reach out. Of course, Texas residents and locals are going to have their voices weighed more. But it is important for the entire conservation community to remind Texas how stupid it is to put a highway on top of a desert wetland.

0:31:00 - (Jon Rezendes): And then we do need partnerships. El Paso is small in terms of our influence, but we are mighty in terms of our grassroots efforts. It took us 52 years to get castnarrange national monument designated, and hundreds of thousands of people have contributed to that effort. That is the way that things get done here. We do it together. We elevate each other's voices. And then sometimes we get lucky and we get a champion like our local representative, Veronica Escobar, who worked tirelessly to get cast in the range on Joe Biden's desk.

0:31:32 - (Jon Rezendes): That might be another situation here where we need partnerships and we need champions to help us. From defenders of wildlife, from the center for Biological Diversity, from the Nature Conservancy, we're out here screaming for help. They're trying to build a highway through our wetland in the desert. They're trying to rezone our land from farm and ranch to industrial so that they can get richer. We are not going to be able to do this alone.

0:31:53 - (Jon Rezendes): And there's a lot of money in California, and a lot of it stays in California. And Texas is not a lost cause. And certainly not far west. Texas. Like I said, El Paso is pretty much New Mexico's biggest city. Anybody who's been to Las Cruces and falls in love with the Oregon Mountains can say just about equally that they've gone to El Paso and the Franklin mountains and that they've seen this amazing wilderness preserved around a city of, again, three quarters of a million people.

0:32:18 - (Jon Rezendes): And I would just encourage more people to learn our story. This is a largely mexican american hispanic community, and communities of color often get passed over when it comes to environmental and climate justice. I'm not mexican. I'm portuguese. I come from Massachusetts. But I would like to elevate the voices of these people in these communities and hope others can hear this call for help from places that maybe have more money or more influence and more connections than we do. I know the friends of the Rio Bosque is open to working with others, and we're hopeful that we can find some type of permanent solution.

0:32:53 - (Jon Rezendes): And I'm hopeful that I can't advocate for the Frontetta Land alliance to take a conservation easement, but I can say that Frontera is prepared to speak with anyone about any conservation easement because that is our mission, is to preserve the land and to preserve open space for all communities. I make that plea that please just learn about us, learn about our story, learn about how wonderful this community is with our grassroots fight and help us. If you have a voice and you have influence, please help us make sure that they don't put a highway through our wetland.

0:33:24 - (Chris Clarke): That's a fantastic way of putting it. I just recently left a job where I was working on campaigns very similar to this. Pretty much out of my 40 hours week, I'd spend an average 60 hours working on things like this. And I know that it's really easy to get entirely focused on the next deadline, the next hurdle that you have to jump. The politics of the moment. I always tried to take myself back to the vision of what we were actually working for in the long term.

0:33:53 - (Chris Clarke): What's your vision for the region in the next 50 years or so?

0:33:57 - (Jon Rezendes): Rewilding is where my heart lays. I was very heavily influenced by Dave Foreman, who recently passed away. He is an absolute legend in my eyes. And he opened my eyes to the fact that the evolutionary process cannot be complete. If we fragment these core habitats, if we take away nature's ability to naturally select, then we are functionally killing ecology as we know it. And for me, I would like to see even more sections of the Rio Grande Valley be rewilded.

0:34:29 - (Jon Rezendes): I would like to see Rio Boscha expanded. I know to the southeast. Right now they are planning a water retention pond for El Paso, drinking water for the lower valley. I think that's a great idea for the water retention pond. The highway would also go through the water retention pond. So think about that. They're talking about a highway over people's drinking water. Again, the stupidity of this idea.

0:34:47 - (Jon Rezendes): But I would like to see the bosque expanded. I would like to see the canals that have been denuded of vegetation and turned into concrete canals so that we can get more water to the farmers. I'd like to see us actually rewild those canals, revegetate them and turn them into corridors themselves in the way that they used to be. And a pipe dream for me, if I could wake up on my 87th birthday and see that the first jaguar was seen in El Paso county in 300 years, that would be heaven for me?

0:35:14 - (Chris Clarke): I was angling for you to mention that your work with the Lobos.

0:35:18 - (Jon Rezendes): Oh, yes, yes. Thank you. No, I love the Lobos, too. I am also a board member of the Texas Lobo coalition. That is an extremely sensitive subject in Texas right now. The idea of returning apex predators. We're actually in the middle of a comment period for mountain lions as well. I will put that as another plug that I want to push. We have a comment period open. Mountain lions are not protected in Texas. If you are allowed to hunt on that property and you saw a mountain lion at 02:00 in the morning, you could throw a rope around its neck, you could throw it in a cage, and you could get your buddies out there for five grand to shoot that animal after you release it from the cage.

0:35:54 - (Jon Rezendes): You could put traps all over your property, and you could let that animal starve and die over a week, and there would be no repercussions for you. Mountain lions are treated like vermin in Texas, and this is a 100 5200 pound apex predator that regulates the herbivores of an ecosystem. And the backwards Texas parks and Wildlife division treats them like vermin. So there is an open comment period right now for people from all over the world, but in particular Texans, to comment until May 22 to propose common sense management for Texas last remaining apex predator. So that is a side tangent, but to me, there's no greater symbol of wilderness than a pack of howling wolves.

0:36:33 - (Jon Rezendes): And nothing would make me happier to know that wolves are running up and down the Rio Grande Valley again, passing between Mexico and the United States. And more than anything, my passion is taking down that dam wall. It doesn't prevent people from climbing it. All you have to do is go on social media and see the videos of people with Home Depot ladders crossing this wall in the desert because they don't have any sensors, they don't have enough personnel on the ground.

0:37:00 - (Jon Rezendes): Again, the wall is a. We talked about a highway as a 20th century solution to a 21st century problem. A wall is a 14th century solution to a 21st century problem. Rewilding the wall is one of my greatest passions, and I'm working closely with the Sierra de Juarez, Collectivo and Juarez. And we have a dream of one day walking from white sands to the dunes of Samoyuka, where they filmed the movie Dune just here in Chihuahua.

0:37:24 - (Jon Rezendes): And we have a dream of establishing a hundred mile or so trail that would take you from. I'll just go north to south, but we could go south to north too. From white sands, the Oregon Mountains, desert peaks, National Monument, the Sierra Vista Trail, Franklin Mountain State park and Castle Range national monument, into the Cerro de Muleros into a freshly protected Sierra de Juarez into the Sierra de San Malayuca, and all the way down to the San Malayuca dunes and make a dunes to Dunes trail.

0:37:50 - (Jon Rezendes): To me, that is heaven, that is the dream. And if we can take down this wall and rewild our world, then that would be my happy 87th birthday.

0:37:59 - (Chris Clarke): That sounds pretty great.

0:38:01 - (Chris Clarke): Hopefully I'll see something like that around my 87th birthday, which is coming up a significant amount sooner than yours. This is a little off topic for El Paso, but February March was my first in depth visit to West Texas and my first visit at all in about 40 years. And I was not sure what I was expecting to see. What I saw made me fall in love pretty hard with that part of the chihuahuan desert.

0:38:28 - (Chris Clarke): But it was really fascinating to me to go further downstream on the river and around Boquillas, just right opposite Big Bend National park, seeing how the border is managed there, which is to say not. And the sort of idyllic, calm, friendly atmosphere that hangs on there. And people are crossing the river illegally or quasi legally in both directions. And it's no crisis there. The biggest crisis I saw is that horses from Boquillas in Mexico were walking into the river and shitting in there and that I just.

0:39:08 - (Chris Clarke): I knew intellectually that the river was supposed to be a lot higher than it is, but people were walking across and not getting their knees wet. But it was just so much of a different image of the border than I had been getting. And I did manage to get to the border in El Paso for a little bit. There's a park a couple miles east of downtown whose name I'm forgetting, a.

0:39:34 - (Jon Rezendes): ascayate lake or ascayate pond.

0:39:36 - (Chris Clarke): That's it. Having that kind of picture of what the border is like in town, Texas, with there's the freeway in between the park and the river, and then whatever border security stuff there is, or going to places like Organ pipe cactus national Monument, where I was just before my visit to El Paso this year. Nogales in Arizona, Sonora is militarized, fortified, and just the idea that here's this place where it's pretty easy to get to from either side.

0:40:09 - (Chris Clarke): And yet there was no obvious security. People from Boquillas were coming across the river and selling trinkets and tamales and empanadas in Big Bend National park. And I was very happy to be able to buy some empanadas before one particular hike because it was exactly what I needed to put in my backpack. It was just such a different image of the border. And I suspect that the future of the border is going to be set by communities like El Paso, Juarez, where people just eventually say, enough.

0:40:43 - (Chris Clarke): But it was such a hopeful moment in this really dire border situation in which inflated crises have become talking points and people are dying as a result of wanting to come and pick lettuce for subminimum wage to send money home to their families. There's no question there. I just. Ranting, ranting.

0:41:07 - (Jon Rezendes): I appreciate the story because you can go here in El Paso county, we have the wall throughout, just about the entirety of El Paso county. But once you get into Hudspeth county, as you're describing, and further down all the way to Big Bend, the river is beautiful and wild. You can cross regularly. And it just reinforces this idea that the proponents of the wall are pushing a culture war, that it is purely a culture war, that this fabricated crisis. I mean, I live on the border.

0:41:36 - (Jon Rezendes): My wife goes to the University of Texas at El Paso in the doctorate program. She looks at the border every single day from her campus. And there are absolutely people that are coming up here seeking a better life. They are not coming here in droves. They're not coming here in waves. There isn't this wall of a million people built up on this fence that's like World War Z, and they're just climbing over the fence in the way that the MAGA world and the wall pushers are describing it.

0:42:06 - (Jon Rezendes): They are fostering fear in a place where there is no fear. It's just, it's so unbelievable the disconnected reality that these people who aren't living on the border are experiencing versus those of us that live here every single day. And you can go all the way up and down the Rio Grande Valley, especially in the lower Rio Grande valley by Brownsville and by Del Rio. I know that's a little further up. But all of those communities up and down Presidio, they didn't want the wall.

0:42:36 - (Jon Rezendes): They didn't want the floating saw barrier that Greg Abbott put out there. These are communities that you're describing and that I had tried to describe earlier, that it is not one community versus another community. A river just happens to pass through a community. And the people on one side versus the other are no different. They speak the same language. Almost everyone around here speaks Spanish, but most folks speak English, too.

0:43:01 - (Jon Rezendes): It is, this border crisis is so fabricated and false, and it's a narrative set up to promote a culture war. To create fear, to create votes. And it's so obvious, and yet the ecological damage that we're creating will take generations and generations to recover from. You look at some of these mountains that they have absolutely defaced in order to build the border wall along it. And one day, I hope that we can look back and look at them as crimes, that we can go back and be like we should be prosecuting these people for crimes against citizens in both countries, for these ideas that they're perpetuating.

0:43:41 - (Jon Rezendes): And I'm hopeful that when these walls come down and we embrace this idea of respect for the land and stewardship, that we'll be able to laugh at these times as we are replanting cottonwood trees along the river on both sides of the border. Yeah.

0:43:55 - (Chris Clarke): A place I used to live in, in Joshua Tree. My landlady had a property across the road from where I lived, and she had an artist friend who took steel from the old bay bridge between Oakland and San Francisco. When they scrapped the old bridge and built a new one that was sized seismically, more sound. And this structural steel that got salvaged from the bridge, some of it got turned into a really beautiful gate at her property. That just is the kind of gate that welcomes rather than keeps out. And I just, I can't shake the idea of the fact that there are all these art supplies on the border that were thoughtfully provided by the Trump administration, that, you know, just a cutting torch and a little bit of creative welding could turn into something really beautiful instead of what it is right now.

0:44:45 - (Jon Rezendes): Agreed.

0:44:46 - (Chris Clarke): I would love to see a time where people were pulling those things down with whatever vehicles are on hand and putting that steel to good use someday. John, we've got a lot here, and I really appreciate you taking the time.

0:45:00 - (Chris Clarke): To talk to us.

0:45:01 - (Chris Clarke): This has been really illuminating and definitely need to do an episode on mexican wolves at some point really soon.

0:45:08 - (Jon Rezendes): I'd love that. Thank you for the platform, Chris. I really appreciate it.

0:45:11 - (Chris Clarke): Yep, you bet. Jon Rezendes, thanks so much for joining us.

0:45:15 - (Jon Rezendes): Thank you.

0:45:47 - (Chris Clarke): Well, that wraps up this episode of 90 miles from the Desert Protection podcast. I want to thank Jon Rezendes for spending time with us and talking about this crucial wetland that might just be the nucleus of a whole constellation of rewilded wetlands up and down the Rio Grande. If saner heads prevail, or at least saner heads than the development happy folks that currently seem to be running things in Texas and everywhere else, I want to thank Jon for spending time with us. Very interesting conversation. If you're interested in finding out more about the Rio Bosque wetlands or Frontera Land alliance or the Texas Lobo coalition, check out our show notes for links. We'll have them there for you. In addition to links that will help you make comments to Texas DOT about not paving crucial remaining wetlands in threatened ecosystems.

0:46:36 - (Chris Clarke): In addition to Jon, I want to thank our most recent new financial supporters, Hillary Sloan, Erna Tobacco, Stacy Goss, an old friend who's one of the movers and shakers behind the Sierra Club's Desert Report, a crucial publication. For those of you following desert issues in California and Nevada, check them out at desertreport.org. Florian Boyd, an old friend and occasional hiking buddy, it's been too long since we've been on a hike.

0:47:04 - (Chris Clarke): Caroline Partamian, who, in addition to tossing some money our way this past month, is also serving on the board of directors of the Desert Advocacy Media Network. Thank you, Caroline. And speaking of having spent time in working class, Buffalo, New York, back in the day, my old buddy Cindee Segal, who is now representing Texas among our donors. Cindy, thank you so much for staying in touch and for supporting what we're doing here.

0:47:33 - (Chris Clarke): I want to thank Joe Geoffrey, our voiceover guy, and Martín Mancha, our podcast artwork guy, our steam song Moody Western, is by Brightside Studio. Thanks for listening. We'll be back next week.

0:47:48 - (Chris Clarke): In the meantime, take care.

0:47:50 - (Chris Clarke): The desert needs you, and we will see you at the next watering hole. Bye now.

0:50:02 - (Joe G.): 90 miles from needles, is a production of the desert advocacy media network.

Jon Rezendes is an influential conservationist with a dedication to the preservation and rewilding of the Chihuahuan Desert region, particularly in El Paso, Texas. His military background brought him to El Paso, where he found a second home amid the natural beauty of the desert landscape. As the Vice President of the Frontera Land Alliance and a board member of the Texas Lobo Coalition, Rezendes is a champion for environmental causes in the region. He is a strong advocate for the protection of the Rio Bosque wetland, a critical riparian habitat threatened by development proposals.