S1E15 What Keeps You Going plus Bristlecone Pines

With bad news all around, how do we keep up our strength and resolve to protect the places that matter? Chris and Alicia start an ongoing conversation in a couple of those places. In between, 90 Miles from Needles talks to LA Times reporter Louis Sahagun about his reporting on a new problem facing the desert's ancient bristlecone pines.

Become a desert defender!: https://90milesfromneedles.com/donate

See omnystudio.com/listener for privacy information.

Like this episode? Leave a review!

Uncorrected Transcript

This podcast was made possible by the generous support of our Patreon patrons. They provide us with the resources we need to produce each episode. You can join them at 90milesfromneedles.com/patreon

Bouse Parker:

The sun is a giant blowtorch aimed at your face. There ain't no shade nowhere. Let's hope you brought enough water. It's time for 90 Miles From Needles, the Desert Protection Podcast, with your hosts, Chris Clarke and Alicia Pike.

Chris

Welcome to 90 miles from Needles. This is Chris.

I am talking to you from the campsite in Joshua Tree National Park, where we will be holding our 90 Miles From Needles. Supporters and subscribers camp out on the weekend of September 9 through 11th. That's Friday through Sunday. And it's a beautiful morning. A little bit of cloud cover. Got a little bit of rain last night and everything looks really clean, nicely washed. There's a Santa Cruz out in the air, a little bit of air traffic above. It's like constant in Joshua Tree National Park these days, being so close to Los Angeles, but it promises to be a good place to hang out to get to know our subscribers, and we look forward to seeing you. This is open to anyone who is a Patreon subscriber of our podcast. You can join our Patreon subscribers at 90milesfromneedles.com/patreon. And we're also going to open it up to anyone that gives us substantial one time donation through our Kofi site. That's 90milesfromneedles.com/Kofi $20. We've opened that site, as we've said before, because there are people that want to give us a little support, but basically don't have the ability to commit to a monthly donation. And we understand we've been there in this episode and we've been hinting at this in the past. But in this episode, we're taking a new approach. This may shape how we do the podcast into the future. We have some potentially upsetting news to report. We're going to be talking to La. Times environmental journalist Louis Sahagun about his recent reporting on a problem that is affecting the ancient bristlecone pines of the desert mountains in California and Nevada. But there's been a lot of bad news, and there will continue to be a lot of bad news, and we will be continuing to report on that bad news. And we are also examining the role that bad news plays in reducing our capacity to actually do something to protect the places that we love in the desert or wherever you happen to live. We're going to be doing our best with this podcast to remind you of why it is we're doing what we're doing in this episode. We're going to pay a brief visit to Alicia's favorite place in the desert, a place that she has returned to over and over again was not too far from here, in fact, in Joshua Tree National Park. And then we'll hear from Louis, and we will then go to one of my favorite places in the desert, a place not far from the Cima Dome, joshua Tree Forest that we covered in our third episode this year, wee thump Joshua Tree Wilderness in southern Nevada. It's a beautiful place. It's a crucially important place for the desert tribes, especially up and down the Colorado River. Focusing on the bad news is often necessary. We're certainly not going to shy away from it, but we need to counter that as well. We need to remind ourselves of the good. I'm talking to you about bad news right now, and there's a desert spiny lizard about 20 yards away from me doing push ups, and it's just lightening my heart, even little things like that. Life is good. I'm not saying that your life is necessarily good. We all have struggles. Some people struggles are harder than others. You might be in the pit of despair right now. What I mean to say is life is good. The phenomenon of life is good. The plants, the animals, the protozoa, the fungi, the organisms that are somewhere in between all of those things. The relationships are complicated, sometimes inconvenient, but it's good. And that's why we're doing what we're doing. And not only is it really important just to remind ourselves of that, not only is it good for your soul, but it's good for your productivity as an activist, you get a lot less done when you're burned out. It's not all about productivity, but that is an important thing to consider. If you don't take time to recharge, remind yourself why you're doing what you're doing and just relax in the good that is around, you get a lot less useful work done. So that's one of many reasons why we're really looking forward to seeing our podcast supporters at Joshua Tree National Park in our free camp out on September 9 through the 11th. You are responsible for your food and supplies and all that kind of stuff, but we will make sure that there is good company and some swag, some snacks. Not only are we looking forward to hanging out with you, getting to know you a little bit better, but we're looking forward to diving into, in more detail, examination of how can we keep going, how can we keep our heads up and keep working when the news all around seems overwhelming, incredibly daunting? It would be easy to throw up our hands in despair, and we don't.

Chris

Want to do that.

Chris

Let's move back in time now, a few days to Joshua Tree National Park the morning after a monsoon storm, and Alicia giving me a tour of her favorite place in the desert.

Chris

It smells so good here.

Alicia:

Yes, guys, it was so humid yesterday. I felt like petrichor was a wet silk blanket wrapped around you. It's so hard to describe. This is where I am most happy in the world.

Chris

Definitely a lot of happy cat claw.

Alicia:

Oh, yeah. You really got to watch out for that going up this canyon. All right. Got some water. Nice and calm. Yeah. This was all raging yesterday. Got some great photos and video. So this is the mouth of that little side canyon I was telling you about. And it just goes up to that wall. Is this okay for your leg?

Chris

Oh, yeah. I did a bunch of miles on San Jacinto with Lara last Friday, and no hamstring issues at all.

Alicia

That's good, right? You just let me know when you don't want to go any further.

Chris

Alicia is taking good care of the old guy.

Alicia:

Well, I've just learned that apparently I'm really bad at reading my hiking partners just in my mind, like, all right, we're going to Rattlesnake Canyon. We're going to the zen cave. And that's that. It's a bit soupy there.

Chris

Yes, it's okay. These are new and still waterproof, so.

Alicia:

Usually I go up that thing, but I'm not so sure about our next step from there because that pool looks filled. We can get up into that little side canyon if you want.

Chris

That works.

Alicia:

And keep going and find some shade up there in the boulders. These conglomerates have such perfect tack for climbing on. It's so lovely. Oh, yeah. So now we'll more snaky territory here.

Chris

Whenever I'm guiding people that are new to the desert, somebody asks me, are we going to see a rattlesnake? And I say, God, I hope so.

Alicia:

Yeah. Okay. So now we're back in the stream bed. Well, there's some water over here on the other side of that wall. It looks like there might be some precious shade over here. Just like a perfect little couch for us.

Chris

Nice.

Alicia:

I brought some ice cold water. Would you like some?

Chris

Sure. That's lovely.

Alicia:

And because I'm in a celebratory mood, I brought myself a beer.

Chris

All right.

Alicia:

Get some extra calories in this girl. Oh, my goodness. What? Glory golly. I can just feel the happiness of this entire canyon after yesterday's event. Oh, my goodness.

Chris

This is a really good delayed coda to the monsoon episode. The issues are still there, but it's awfully nice to have a spot where I might have gotten enough water to carry it through for a few months.

Alicia:

Just seeing that water percolating so quickly into the Earth, it was such a comfort to see that the earth was getting a good drink.

Chris

We're in the shadow of a great big boulder that is keeping the sun off of us, but it's not big enough to keep the wind from blowing around it. So we're getting a very nice little breeze here. I feel like over the quarter century that I've got on you in Desert Adventures, accumulated a bunch of different places. Some of which I've shown you. And it's always been fun and just sinking in that this is your super double special, extra personal place, and I'm just really pleased that we're here together.

Alicia:

Yeah. I finally got you here. This was the place where Ted brought me on the first overnight trip we did together. He brought me out here and we stayed up all night and drove to Indian Cove and watched the sun come up. And Tad and I really fell in love out here. We've got such a symbiotic formula. I always lead going in, he always leads coming out. It's a very natural relationship with nature out here where we both have so much to offer in different departments. It's really amazing to see his technical skills and my natural knowledge and all of that kind of come together. And this is just like everything to the foundation of falling in love with dad was he brought me here and I've spent most of my desert hiking time in here. Definitely. This is my space. This is where I want to be.

Chris

For the benefit of people who aren't familiar with Joshua Tree National Park or with maybe even the desert at all, how would you describe where we are? How would you describe Indian Cove?

Alicia:

This is the termination of the Wonderland of Rocks, which is a large white taint Monsa granite formation that looks like a giant comma that runs through Joshua Tree National Park.

Chris

We're on the north side of that?

Alicia:

We are on the north side of that. So this is the terminus of the Wonderland of Rocks on the north side. And this is where it meets the desert floor. And it's a canyon with a lot of stories. There's so much written into the rocks, literally and figuratively and academically. You could spend a lifetime in this canyon alone. But, yeah, I would describe it as gosh, there's so much going on here. I call it the Queen Mountain Complex is butting up against the White Tank Monzogranite Formation. And where they meet is this giant canyon. And this waterway just slowly winds off into the open desert and terminates eventually. Where I'm looking now is a view of all the wonderland of Rocks. And it's mind boggling out here. These formations that set off from the main clumps are called Inselbergs. They're like rock icebergs. And I just love the sea of Inselbergs out there and the endless opportunities to explore and feast my eyes upon beautiful rock formations.

Chris

The place where I lived before, the house in 29 was half a mile from another section of the north edge of the wonderland. And it was really remarkable to go hiking up into the park, hopping the fence in the park boundary. There are little trails up that way, so it wasn't really doing damage to the resource, but just getting onto the slick rock and walking around these big boulders that are sitting out there in the middle of dissected desert plain. And you just come to this boulder that's the size of a five story building, and all the microclimates form because the rubble and debris from hundreds of years of erosion accumulating on the north side of the boulder would provide shade and a little bit extra moisture.

Alicia:

You get ferns and lichens and succulents living on the right side of these rocks. Ferns, that's one thing that surprises people. I have a fern stop on this canyon where I like to share the beautiful ferns that grow in these boulders. Such a delicate thing in such a seemingly harsh environment. Do you want to go back to where we saw that pool, or do you want to get a little bit further upstream?

Chris

Why don't we check out downstream?

Alicia:

Yeah, that big sand bank is a nice place. The action on these rocks, everywhere I look, there's a story to be told, whether it's geologic or whether it's mechanical weathering. I see these giant rocks fractured in half, and I know that's just a mechanism of ice freezing and expanding. And then slowly, it's like a chisel, just these big rocks just split in half. It's not a mystery to me, but I just love reading the stories that the rocks have to tell us. And the varnish. I could go, oh, man, I love these rocks more than anything. So if you look to the left, this is like where we started, and then we dropped down into the riverbed. So we can either pop back over these rocks into the river bed, or we can walk out. We wanted to go downstream right out the willows. That last bit right there, I don't know if we can get through. I'm thinking maybe we should go back up and just try and pop back down. That works without all the bolters.

Chris

I don't mind getting my feet wet here and there.

Alicia:

I'm of the faction who does it only if they have to. Not a big fan. I've already got a soaking wet pair of boots at home drying out from yesterday's adventures. Yes, I've had my fill of soaking my boots for today, so I should do it. Like, why not? It's fun. How often do you get to walk through water? Because you can't get downstream in the desert.

Chris

I spent a lot of my preteen years walking up and down creeks in upstate New York. Usually my shoes off, and this reminds me of it a little bit, but not very much.

Alicia:

It's a reach, but there's trigger memories there.

Chris

Yeah.

Alicia:

I'm going to leave my backpack here. I'm just going to pop over on that conglomerate and have myself a moment.

Chris

Coming up next on 90 Miles from Needles, Alicia has herself a moment. It's a gorgeous little taste of a place really special to someone that's really special to me.

Alicia:

Yeah, this is a special place far beyond me. I'm just very attracted to it. Plus, it's 3 miles from my house, so that helps.

Chris

At the end of June, the Los Angeles Times published an article with some quite disheartening news about the forecast for survival of Bristlecone pines. Bristlecone pines are actually two species of pines that live in the very high reaches of mountains in the arid west, which are known for not only they're living essentially above treeline in those mountains, beyond the reach of other pines, but also for the incredibly advanced ages they can reach. The oldest known living pine, nicknamed Methuselah, which is growing in an undisclosed location in the White Mountains in California. It's undisclosed because scientists fear that if they publicized its location, some yahoo would come by and set it on fire. Anyway, methusela's age has been calculated at just under 4800 years, which is pretty impressive for something that's not a colonial desert organism. Not bad for a tree that's respectable. It's doing just fine. It's done a really good job, that methusola tree. At any rate, bristle cone pines are facing a new threat from insect invasion and fungal disease. And the Los Angeles Times veteran reporter Louis Sahagun on June 27 put together a report that opened a lot of eyes about an unanticipated effect of climate change.

Chris:

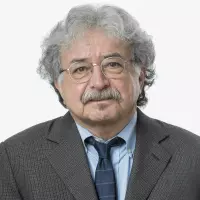

We have in the studio with us Louis Sahagun, a longtime reporter on environmental and other issues at the Los Angeles Times. He has a Pulitzer Prize to his credit. Lewis, thanks for joining us on 90 Miles from Needles.

Louis Sahagun

Thank you for having me.

Chris:

So in late June, you had an article that came out that was rather astonishing and I have to say a little disheartening about mortality in the famous bristlecone pines of the California desert mountains. How did you latch onto the story? What happened to bring it to your attention?

Louis Sahagun

This article is about a sad emergency that I learned, incidentally, while talking to a spokeswoman at Death Valley National Park about their long and troubled efforts to get rid of boroughs in the park. And there wasn't much news to advance what I'd written before, which is essentially there's a whole lot of boroughs. I'm still there. There's thousands. Anyway, when I was done, I said, as I always do to my sources, in every conversation I have with sources, I always end up with anything else going on, anything else I should know about? And the spokeswoman at Death Valley National Park, there was a long pause, and then she said, maybe. I mean, there is this study it's showing, unfortunately, the bark beetles and drag are killing Bristlecone pines. Then there was another long pause, and I said, what? What? Tell me more. And then that led to a peer reviewed scientific paper that I got a hold of by US. Forest Service biologist Candace Malone, Barbara Benz that came out early recently detailing the discovery of these ancient trees which don't die of old age but can be killed by drought and bark beetles and which is exactly, unfortunately, what was unfolding. They discovered on the top of Telescope Mountain in Death Valley National Park and in forest in Bristlecone pine forests in southern Utah. I got a hold of Candice Miller on the phone and I asked her, so you're the one, I believe, who discovered this problem. What do you see? And she said, There are hundreds, maybe thousands dead on Telescope Mountain. And I said, Wait a minute, Candace, those trees are thousands of years old. How long did it take to kill these trees? Decades? 100 years? She said, a couple of years. So these are trees that lived through almost magical, almost biological adaptations over millennia, being killed by bark beetles and doubt in a matter of just a few years. And it's getting worse. It's spreading, this problem. So there's actually a lot of intrigue of sorts in this peer reviewed paper because it concludes with recommendations for dealing with this problem that's spreading and is only 70 miles away at this point that we know of for sure from the Cherished ancient Bristlecone Pine forest and the White Mountains visited by thousands of travelers a year. The paper concludes with a call to arms among federal land managers who have Bristlecone pines within their jurisdictions. This is happening, it's new, it's killing the trees. We have to do something about it. We have to arrive at some kind of scientifically based war footing of sort. Which won't be easy, though, especially in lands that are designated as wilderness, with wilderness protections and the like. But the paper raises the specter of drought and bark beetles killing one tree after another all the way up to the immediate vicinity of the Methuselah tree, the oldest tree that we know of, or believed to be the oldest. I know it may well be still, although there are scientists in Chile who have announced the discovery of an ancient cypress street there that may be 600 years older than Methusel. But in any case. They suggest that if it comes to pass that bark beetles and drought hop from host trees like pinion pines and limber pines which live in the vicinity of Bristlecone pines If they hop scotch from those known host trees to right up to near Saint Method. Then federal land managers have to think about dropping down. Removing the limber pine host tree with bard beetles ready to swarm onto methuselah. That's an interesting problem because it raises anthropomorphic complications, including just for example, wait a minute, folks. Are you putting a higher value on a Bristlecone pine because it lives only a few thousand years longer than a limber pine, which grows to be 3000 years old? So it's expendable in your mind. These are really tough questions that have to be answered and they have to be answered soon.

Chris:

So presumably the limber pines and the opinions and such have been there for a while, and the bark beetles have been trying to make a living on those pines for presumably centuries, millennia, et cetera. So what's different now about the interaction between the limber pines and the Bristlecone pines ?

Louis Sahagun

Actually, there's a fascinating difference. What's different is that over the last several hundred years, which is a few minutes in Bristol pine time or limber pine time. Climate change has enabled Clark's nutcrackers, a bird that lives up in those high altitudes, timber life.

Chris:

One of my favorite birds, in fact.

Louis Sahagun

Yeah, they have a habit of collecting nuts and storing them in locations, burying them for later times, tough times, down the line, down the road. Clarks nutcrackers have been moving and storing seeds over the last few hundred years because of rising temperatures. They're storing seeds up there by Bristlecone pines , but the seeds now are growing. They started growing, I should say, into limber pines that now are hopscotching, even over a mid and beyond, higher still than Bristlecones. Okay, so now these are mixed for us. They weren't just a short time ago, but they are now. So now they're mixed for us. The bristle compounds are not alone up there. Due to climate change, rising temperatures, and liverpoints host bark beetles, they have moved into the neighborhood of Bristlecone pines and they brought their problems, biological problems, with them.

Alicia

Can you tell us if bark beetles are native to this area, or are those something mark coming somewhere else?

Louis Sahagun

Bark beetles are ubiquitous, but pine trees over millennia have evolved mechanisms internally that have always prevented bark beetles from killing them. They would only get so far into the outside layers of the trees and limbs. What's happening now is that bark needles that are killing lumber pines, opinion pines, and other chase, they're now swarming onto Bristol pines, boring into the outer layers, into the cambium that delivers water to leads and from leads to roots, back and forth. And although bark beetles do not fulfill their life cycle in a Bristlecone pine, they do enough damage in the Larval states to invite a blue stain fungus, which is lethal and to choke October delivery circulatory system of the tree. And it doesn't take long for it to happen. It'd be a problem. It's a new sad tragedy.

Alicia

I was reading in your article that the Bristlecones had a reaction of drowning insects and SAP.

Louis Sahagun

Was that yes, that's correct. But how is that oh, it's not enough. It's not enough because of stress from drought and these other neighboring trees bringing hordes of bar beetles in that are finding their way into the tree. Although they don't, as I say, complete their life cycle is they don't turn from Larva to Beetles, but they do enough damage in any case to kill the trees.

Chris:

So aside from sending out the limber pines, are there other ideas that the biologists have for ways to combat this? Are there diseases they could put in the bark beetle population or some kind of sterile male technique like they used to do with screw flies in Texas and things like that?

Louis Sahagun

The answer right now is no. Although some of these notions have come up and even reached the decision making rooms of federal land managers and their scientists. For example, one idea that came up shortly after this discovery was okay, let's put we know what sets we can use, we know what biological bathing systems we can attach to in these trees forests and will kill any and all bark beetles in the area. But that was scotched almost immediately by federal forest pathologist who said what you're going to do if you try and lure them into traps is you're going to invite every bark beetle for hundreds of miles away from the party. You don't want to do that. Bad idea. So short of that for the meantime, because these trees really are so important in so many ways, not just because of the magical feats they perform on their own, but also culturally, right? Most people learn to admire them through photos by Ansel Adams so short of anything right now that they can do, and short of chopping down neighboring trees in wilderness areas just because they're a little younger and expendable, therefore the word is out to be on the alert. Here are signs of trouble. If you see this, report it, and that's where we are right now. Whether it'll be enough, I don't know. It only takes a few years to kill trees that have with changes from ice age to severe drought and more and a few years to kill them. There is no answer right now.

Alicia

Is there any estimation based on the percentage of trees that are left and how quickly this is eradicating them? Is there an estimation on how long we have to fight this fight against the bark beetle?

Louis Sahagun

There really isn't. There really isn't. But it is a crisis nonetheless because the problem was discovered on a mountain in Death Valley National Park that's only 70 miles away, which is really nothing. The drought, a second round of drought persists. We're in the third year now of what scientists are telling us is the most severe drought in 1200 years at least. And this comes follows by just a couple, two or three years, what was previously regarded as the worst drought and recorded history, the drought between 2012 and twelve and 2016. So we have back to back severe droughts and there's no indication that this one is going to end anytime soon. So what does that mean? It means that there is a palpable lethal danger that was previously unknown and that arrived quickly, is taking a severe toll in just a couple of years, trees that weren't supposed to die otherwise. And because of legal complications and federal protections, I believe it will take a while to come up with a formal strategy for curtailing the advance of bark beetles, carrying with them lethal doses of blue stain fungus.

Alicia:

After several decades of reporting on environmental issues that can be downright depressing. What keeps you going at the end of the day.

Louis Sahagun

When I was two years old at my parents farm workers camp in what is now known as Whittier Narrows east of downtown Los Angeles back in the early fifties. It being there. Imprinted in my mind scenes of wildlife on a scale and densities that I will never forget. Frogs, birds in the stream, the real Honda. The reason I bring this up is because as the years went by, I saw less and less patches of greed and water with living things in them. And so what propels me, I keep chasing those memories, looking for signs that their vestiges, be it in downtown La, by way of, believe it or not, a family of Lender salamanders that I found once under boards under my grandmother's tortillon. Whittier Boulevard in East La. A family of slender salamanders, of all places there, or be it Bristlecone pines on these windswept slopes above 11,000ft in the White Mountains. I look for what's working and what isn't. I look for one more place, maybe in the San Gabriel Valley where coachwhip snakes can still be found in spring. That's incredibly exciting to me and it keeps me going. I hope that makes sense. That's a great answer, but that is it. It was those earliest memories of all in my mind of Whittier Narrows as it existed in the early 1950s and around at Sanghara Mountains. And there was a lot of green in those days in Southern California. I've been looking for places where those scenes, however small in some cases, continue to persist.

Chris:

Louis Sahagun, thank you for joining us today.

Louis Sahagun

Oh, thank you very much.

Alicia

02:41 p.m. On a Saturday afternoon, sitting in the Wee Thump Joshua Tree Forest after a fun day of exploring a plant sale, walking Box ranch and then making some new friends and heading out to Mystery Ranch, getting a little tour over there.

Chris

It's really gratifying when you go to a place thinking that maybe if you're lucky, you'll find somebody who will be interested in hearing about the podcast and will take a sticker from you. And then you get there and it turns out that half the people there are avid listeners to the podcast.

Alicia

That was pretty heartwarming.

Chris

That was freaking awesome. And yeah, just a really good day in the desert. And we are sitting, as Alicia said, at the We Thump Wilderness. We're just outside the wilderness. There's a dirt road that goes around the edge of the wilderness and we're just parked on the nonwilderness side of that. Just a beautiful stretch of Joshua Tree Forest with crease out and bunch grasses and choyas and barrel cacti. Don't see any barrel cacti right now, but I know they're in there because this is one of my favorite places. We got a little bit of rain on us earlier, which stopped the conversation and we all went outside and stood in the rain and silently pagan worshiped the rain.

Alicia

I love how when nature calls Alicia, she just has to answer. And everyone in the room could see that I was struggling to pay attention. And I remember saying, it's raining. Whenever this happens, I got to go outside. And we all, gleefully were like, yeah, let's go outside. That was fantastic. Feel cold. Just more than a slight breeze, but the slight rain and a chilling breeze.

Chris

This is such a wonderful place. In 2008, when I moved to Nipton, which is not far away, just on the other side of the state line, when I moved to the desert full time for the first time, I would come here and I would sit or I would hike. I'd find barrel cacti in bloom, would get to know the Joshua trees. I would walk up and down the washes. Ran into a northern Mojave rattlesnake on one walk. That was the first time I'd ever seen one. that was entertaining.

Alicia

Always exciting to run into a snake.

Chris

It rattled at me very politely from about 20 yards away and then settled down. I used to come up here and sleep when it was too hot in my house in Nipton, because this is a couple thousand feet higher and it's.

Alicia

Still for an overcast day, it's still quite toasty. What would you say?

Chris

Yeah, it's warm. And we did get that rain a little bit, so the humidity is up a little bit. Yeah.

Alicia

This is my first time here. Thank you for bringing me here, Chris.

Chris

I wanted to show it to you ever since we were recording some of that stuff for episode three on the Cima Dome fire. When you saw the devastation of what used to be, and there were little hints of what it used to be like there. But I have just really wanted to show you this because this is what I remember that being, and I find it restorative. And it's just really important to remember to hold on to the things that keep you going. This is a beautiful place. And coming here, there's always something to learn. There's always some connection to be had. Always a way to recharge your batteries.

Alicia

It's something that we ask ourselves fairly regularly. What keeps you going, doing the work that you do, or just being alive. And places like this in nature, they are the reset button. They are the recharge. Your battery plug in. And it's protecting and fighting for places like this that should keep any activist going, that's fighting for the desert. To see something like this and to know places like this are at risk all the time of development, it increases your appreciation for what you have. And I'm so grateful for how much of the desert is still intact.

Chris

It is the most intact ecosystem in North America, south of the tundra. And that's just this huge area that settlers society, industrial society didn't see much use in. There wasn't any reason to plow it. There wasn't any reason to dig up all the sod and put in corn or wheat. There's just so many millions of acres of this same kind of beautiful, intact, wild landscape.

Alicia

Not all humans think about having access to this kind of vast tract of intact wilderness. I think about people who are born and raised in places like New York City, Paris, London, Rome. They've been building up for so long, and they've created everything that you need in a close radius, and it's meant to be self contained. You don't need any more than what is there provided for you. They feel like perhaps that's part of society's scar is removing the need for places like this. And that's what really keeps me going, is we need nature. We are part of nature. And I feel enthusiastic about defending it because I know how valuable it is to my life. Even just me saying that makes me feel exploitative. I need this for me.

Alicia:

I need this.

Alicia

But as an animal, yes, you do. You do need this. And I know people from all over Europe come to this part of the desert because they are just infatuated with its mysticism, with its vastness, with its treachery. It is so primitive. It makes me feel whole and complete.

Chris

We are so lucky compared to all those poor Parisians.

Alicia

And I feel like that could be debated because man access to fresh bread and food, really good food, you can't just walk down the street and get a divine cappuccino and a loaf of bread. But I can walk out my door and look at unimpeded, untrammeled wilderness. So I'll take my wilderness over a good cappuccino and a baguette any day.

Chris

I don't even need to walk out my door and I can get some of the best shots of Espresso ever pulled in the US.

Alicia

There you go.

Chris

I just think about what this place has meant to me. Not just this place, but the entire desert. It was here for me when I needed it. I had no idea what my life was going to be like at that point. It was 15 years ago, approximately, and I felt really old back then. I felt like my wife was drawing to a close. And this place this place just made me feel like there was so much of life still to happen and I was just getting started. And the thing is, there are so many places like this. There's just this connection. I always feel like I'm lapsing into mushy headed hippie speak when I talk about it, but there's a kinship here. You sit here and you're surrounded by family and you can relax, you can breathe.

Alicia

One of the things I really like about being in a place like this, with so much wilderness around, is the level field gets evened out. In a way. All the advantages of being a human get stripped away when you put yourself out here without any of those tools or tricks, and no one is judging you, no one's holding you to any bar other than, are you alive?

Alicia:

Or not.

Alicia

I've always loved how nature can strip all that away and narrow your focus to breathing that's it. As much as the next guy. I love mind altering substances, but I've always been fascinated how when I get out into deep nature, I don't want them, I don't think about them, I don't need them. It is a drug on its own. Like a hallucinogen will force you to focus on what might be going on inside your mind. Nature forces you to pay attention to your body right now.

Chris

We were just having a conversation earlier about creosote clonal rings and mojave yuccas that make clonal clumps and they get really old. And just thinking about that and especially going to see them and going to spend time in the presence of plants that are that old and it really reminds me that stuff like annoyance over a meeting not going as positively as I would have liked is really ephemeral and pointless to worry about.

Alicia

Certainly never have a meeting with nature where I feel like that could have gone better. Even my worst meetings, I've learned so much.

Chris

It's really hard getting the other species there to take notes, though, I'll say that.

Alicia

Do you want to get out and walk around?

Chris

Yeah.

Chris

Well, we did go walk around and we got some more recording done among the Joshua trees. And you'll hear some of that in an upcoming episode. Because while we found Joshua tree wilderness is protected, the landscape that surrounds it is still vulnerable. And a group of desert protectors among them. The friends we made that day is working to bring the area permanent protection. And we are already planning an episode talking to them. And that's some good news right there. That right there is a reason to keep going on because when people come together to celebrate a place that means something to them, amazing things can happen. Sometimes the landscape itself will rise up and nudge you in the right direction, like SEMA dome and we thump. Joshua tree wilderness did for me, like Indian cove did and keeps doing for Alicia. The story of Wisconsin neighbors in southern Nevada coming together to build a new layer of protection is inspiring us and we think it will inspire you. And besides, it's an excuse to come back to one of the finest bits of mojave desert landscape around. Not that either one of us really needs an excuse. That's it for this episode. We hope to see you in Joshua tree in September. Check out our patreon site at nine zeromilesfrometales.com patreon and our kofi page at 90 miles from needles.com kofi. Tune in later in August. Our next episode will be an update on one of the west's largest bodies of water and why it's disappearing and why it doesn't have to. And we'll have good news in there, too. Thanks so much for listening. Can I hand it over to our robot? Announcer now take it away. Baus.

Bouse Parker:

This episode of 90 Miles from Neil's was produced by Alicia Pike and Chris Clark, editing by Chris podcast artwork by our good friend Mortine Mancha. Theme music Is by Brightside Studio other Music by Slipstream Follow us on Twitter on Instagram at 90 mi from Needles and on Facebook@facebook.com. ninetymiles from Needles. Listen to us at 90 Miles From Needles.com or wherever you get your podcasts, thanks to our newest Patreon supporter, Marissa Monroe, and our very first Kofi supporter, Robert Bagel. Support this podcast by visiting us at nine 0 mile from Needles. compatrion, and making a monthly pledge of as little as $5. Or visit Nine 0 Mile from Needles.com Kofi to make a one time contribution. Our Patreon supporters enjoy privileges, including early access to this episode and an exclusive Joshua Tree National Park campout in September 2022. Crucial support for this podcast came from Tad Kaufin and Laura Rosell. All characters on this podcast, together with the Snoring, Chihuahuan and Great Basin deserts, form a larger North American desert. This is Bout Parker reminding you not to drive across a flooded wash no matter how much of a hurry you're in. Unless you're in a hurry to discover what happens after you die. See you next time.

Chris

Sit heart. Sit. Good dog.

Louis Sahagun

Louis Sahagún is a former Los Angeles Times staff writer who covered issues ranging from religion, culture and the environment to crime, politics and water. He was on the team of L.A. Times writers that earned the Pulitzer Prize in public service for a series on Latinos in Southern California and the team that was a finalist in 2015 for the Pulitzer Prize in breaking news. He is a former board member of CCNMA: Latino Journalists of California and author of the book “Master of the Mysteries: The Life of Manly Palmer Hall.”